Notes toward Proto-World, Part 2

[Previously: A speculative ethnolinguistic family tree of non-African (and some African) humanity; or, notes toward Proto-World, part 1]

Let’s take a closer look at some of the less intuitive branches of my tree from part 1.

Return of the Siberian clade

The linguist Michael Fortescue once argued for a Uralo-Siberian language family that included Uralic, Yukaghir, Eskimo-Aleut (aka Eskaleut), and Chukotko-Kamchatkan, but he later expelled Chukotko-Kamchatkan.1 I’m bringing it back and throwing in Turkic as a bonus (but discarding Eskaleut, which I think is just a northern Native American language, reflecting proto-Eskaleuts’ origins in the Ocean Bay culture of Kodiak Island and the Alaskan Peninsula — a topic for another day, maybe).

The recent preprints Zeng et al. 2023 and Gill et al. 2023, along with a Tabin et al. 2023 poster, helped to clarify the previously murky picture of Siberian ethnolinguistic history. Here’s what I think happened:

More than 8,000 years ago, a group of people from the northern part of the Central East Asia subrealm, belonging to the (initially) East Asian Y-chromosomal haplogroup N, moved into the taiga region east of Lake Baikal and mixed with Northeast Asians, creating the Transbaikal_EMN cluster.

Mixing further with the “Asian Americans” of the Syalakh-Belkachi culture in the taiga, they created the Yakutia_LNBA cluster, initially centered on Lake Baikal but soon venturing out into a wide swathe of the taiga. To the far east, they gave rise to the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages of western Beringia (on top of an Asian American substrate). Heading west, ultimately as far as Scandinavia, they gave rise to the Uralic languages.

Back home near Lake Baikal, though, they were caught up in the influx of Scythian people and culture during the Iron Age. Somehow — helped along by having that dog in them, no doubt— their male lineages survived contact with the horse nomads. In fact, it seems like they married into the Scythian world, creating the Sargat culture2 to the west (a forerunner, I suspect, of the Bulgar/Chuvash branch of the Turkic language family) and the “nuclear Turkic” languages to the east.3 One branch of nuclear Turkic then spread far and wide with the Göktürk Khaganate.

The Avars, I suspect, were the ethnolinguistic “brother” clade of the proto-Turkic speakers, although, like other steppe confederations, they were genetically mixed. (Scrutinizing a PCA plot from Maróti et al. 2022, it looks like the modern-day groups most similar to “Avar_Asian_Core” — presumably the Avar elites — are the Turkic-speaking Yakut. Ancient Avar samples also share their specific N Y-chromosome haplogroups with Turks and Kazakhs, among others (see Ilumäe et al. 2016).)

This helps to make sense of a strange historical anecdote: supposedly, Göktürk representatives told the Eastern Romans circa 600 CE that the self-styled Avars weren’t really Avars but rather “escaped slaves of the Turks.” The Göktürks weren’t lying. It seems that what we call the Rourans of the Rouran Khaganate “most likely called themselves Avars” (Gnecchi-Ruscone 2022) — but these true Avars were Mongolic-like, not Turkic-like. Sorry, Pseudo-Avars: our Northeast Asian culture is not your prom dress!

Stop trying to make Altaic happen

If the Turkic language family is ultimately ethnolinguistically Central East Asian, as argued above, then the notion of uniting it with the Northeast Asian Mongolic and Tungusic language families in an Altaic macro-family is probably dead on arrival. (This view aligns with the conclusion of Okamoto 2021: “Mongolic is likely related to Tungusic or Turkic, but not both.”) But, as a consolation prize, I think that the Mongolic/Tungusic mini-family should be supplemented with the language “isolate” Nivkh, spoken on the island of Sakhalin and the lower Amur River in the Russian Far East. Nivkh has been linked instead to Chukotko-Kamchatkan, but this is probably because the proto-Nivkh absorbed some Chukotko-Kamchatkan speakers during the spread of the Okhotsk culture. But, like (male) Mongolic and Tungusic speakers, the Nivkh retained their Northeast Asian C2a1 Y-chromosomal lineages and, I assume, their Northeast Asian language.

The Upper Tigris macro-family (and friends)

While ancient-DNA analyses have shown that the earliest agriculturists in Iran (more specifically, the northwestern Zagros), Anatolia, and the Levant derived most of their ancestry from local hunter-gatherers in their respective homelands, I think that the first bits of data from ancient Mesopotamia (Lazaridis et al. 2022, Altınışık et al. 2022) paint a somewhat different ethnolinguistic picture. My best guess: The goat domesticators of the northwestern Zagros mixed with Anatolians in the vicinity of the Upper Tigris, in roughly 2:1 proportions, and created famous early monumental-ish sites like Boncuklu Tarla and Göbekli Tepe. As one branch of this Upper Tigris group spread further west into Anatolia (and ultimately, beyond that, into Europe), the distinctive Upper Tigris ancestry became heavily diluted by Anatolian hunter-gatherer ancestry — yet culturally and linguistically these were still Upper Tigris people, whose descendants spoke Hattic/Hattian. Back in the east, the Upper Tigris people spread north toward Armenia (where Hurro-Urartian formed) and beyond that into the Caucasus (already occupied by Kartvelian speakers4), giving rise to the Shomu-Shulaveri culture and ultimately the North Caucasian language families. Meanwhile, down south, the Upper Tigris people colonized Mesopotamia and created the Sumerian civilization. All powered, initially, by goats.

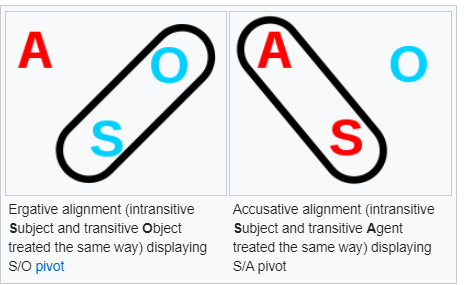

I first came across the concept that all these language families were linked in a 2017 blog post written by, I think, another amateur history and language enthusiast. He pointed out that a suspicious number of putatively unrelated Near Eastern languages are “ergative” — a linguistic property that has something to do with the treatment of transitive and intransitive verbs. This Wikipedia diagram apparently explains it, but I’ve never had the patience to really make sense of it:

Academic discourse also contains hints of (parts of) an Upper Tigris macro-family: there are apparent affinities between Hurro-Urartian and Northeast Caucasian; between Hattic, Minoan, and Sumerian; and between Hattic and Hurro-Urartian. None of these ideas seems to command anything like a scholarly consensus, but sometimes where there’s smoke there’s fire. I would bet that an ergative proto-language spread with animal domestication and that something like Mesopotamia_PPN ancestry can function as a tracer dye to reconstruct its migration.

In praise of Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay

There’s already a soft consensus, I think, that the people of the Indus Valley Civilization spoke a Dravidian-like language, though it doesn’t seem to be treated as established fact. But let me take a moment to celebrate the work of one Bahata Ansumali Mukhopadhyay, who is, as far as I can tell, an independent hobbyist researcher living in India. In my eyes, at least, his 2021 paper established, in amazing, obsessive detail, based on the etymology of various words for “elephant” and “toothbrush tree” and “tooth,” that the Indus Valley Civilization did indeed speak Dravidian. It sounds crazy, but it works.

But the Indus Valley Civilization was ethnolinguistically Iranian (on top of an Anadaman-like “substrate”). So I endorse the “Elamo-Dravidian” theory: people from the Southern Zagros, whose descendants included the Elamites, migrated across the Iranian plateau some 9,000 years ago, built Mehrgarh, and then crossed into South Asia and built Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. Native South Asian hunter-gatherer languages were basically wiped out, maybe even before the Aryans showed up much later. I’m also tempted by another fun “independent researcher” argument: that Brahui, conventionally classified as a Dravidian language but spoken natively only in Pakistan (fairly far away from “core” Dravidian), should actually be regarded as “Modern Colloquial Eastern Elamite.”

Rise of the snail boys

This last bit is probably the most dubious part of my tree, but I’ve talked myself into the following scenario. Around the end of the Ice Age, a group of people from the Levant spread into north Africa all the way to Morocco, bringing with them the Iberomaurusian lithic industry. They also liked eating snails:

Only after Heinrich Event 1, with the climatic ameliorations of the Greenland Interstadial (GI) 1 (around 16-15 ka cal BP), the amount of data increases throughout northwest Africa. During this warmer and moister phase, substantial changes occurred in many aspects of human behaviour and settlement dynamics. One of these is represented by the rapid accumulation of massive midden deposits composed of high proportions of land-snail shells (so-called escargotières) that seems to document an important change in subsistence strategy.

( There’s actually an argument that snails should be considered the first domesticated animal (“heliciculture”)), which I find too beautiful to ruin with closer scrutiny.)

Genetically, these snail boys were something like 60% Natufian-like (pre-Neolithic Levantine), 40% Hadza-like (East African hunter-gatherer),5 but their Y chromosomes seemed to be solely Levantine (nested firmly inside haplogroup E) — another apparent instance of male-dominated takeover.

Then, during the Green Sahara period, the Iberomaurusian snail boys moved south, toward the Sahel and Senegambia, where they again “mixed” with the locals in male-dominated fashion. A recent preprint shows that the ancestry of the present-day Fulani ethnic group can be modeled as a mixture of ancient West Africans and ancient Iberomaurusians.

While the scholarly understanding of the exact internal structure of the Niger-Congo language family remains unsettled, there’s a credible argument from linguist Jack Merrill that Niger-Congo originated on the Atlantic coast of West Africa and that Fulani might have been the first sub-family to branch off:

I think this all coheres fairly well: an early Levantine migration into North Africa managed to extend into the Green Sahara, take root in West Africa, and ultimately give rise to the later massive Bantu expansion. Examining Wikipedia’s list of Y-DNA haplogroups in populations of Sub-Saharan Africa, it’s clear that there’s a strong association between haplogroup E and Niger-Congo, with e.g. Niger-Congo-speaking Wolof and Fon males falling almost entirely under E and Nilo-Saharan-speaking Dinka males falling mainly under the more ancient African haplogroups A and B. Perusing the trees on YFull (painstakingly but non-rigorously), I was struck by how lineages would flip from Levantine/Arabian to African. For instance, E-M78 is found in Neolithic Jordan, Hellenistic Lebanon, and Pharaoh Ramesses III himself — but its brother clade, E-V2729, from which E-M78 split ~19,000 years ago (at the end of the Ice Age), is found in modern-day Fulani and Mandinka people in Gambia. After millennia of admixture with a wide variety of peoples, the Niger-Congo speakers of Africa are nearly entirely African in ancestry, but in my “ethnolinguistic” sense they are descendants of the ancient Levant.

Fortescue, “The Uralo-Siberian Hypothesis,” in Mid-Holocene Language Connections between Asia and North America (2022).

Note that Gnecchi-Ruscone et al. 2021 describes the Sargat samples as Scythian-like but with a small (~5%) contribution from a Siberian-like source. The Sargat samples also carried N-haplogroup Y chromosomes, so I suspect that the small Siberian-like component represents Yakutia_LNBA-like males who mated with Scythian females.

The most reliable Turkic language phylogeny, which I say based mainly on vibes, is Egorov et al. 2022, available via Academia.edu.

The Caucasian hunter-gatherers who mixed with EHG/Sidelkino people to form the proto-Yamnaya probably spoke a Kartvelian language, which is why there’s some evidence of a Kartvelian substrate in proto-Indo-European.