“It was then that men began to invoke YHWH by name” (Gen 4:26)

The real (?!) story of Moses and the Israelites, part 1.

As a lifelong atheist, I come to the Bible as an outsider, but, when I first learned about the documentary hypothesis — the idea that the Pentateuch (comprising the first five books of the Bible) was stitched together out of four originally standalone source documents, known as J, E, P, and D — I was fascinated both by the modern scholarly work that created the theory and by the ancient scholarly work that created the Bible itself. Recently my interest in the topic was rekindled when I was pointed toward the writings of Richard Elliott Friedman, a Bible scholar who has argued that — contra those who harp on the lack of physical evidence for a real, historical Exodus — there really was a migration from Egypt to the land of Canaan. The twist: the migration involved only the Levites, just one of the twelve tribes of Israel, who were assimilated by the original 11 tribes and who brought with them the worship of a god named Yahweh. There’s a short version of Friedman’s case at TheTorah.com, but I couldn’t resist getting my hands on his book The Exodus, along with his earlier The Bible with Sources Revealed (which presents the text of the Pentateuch using different formatting for each theorized underlying source document) and The Hidden Book in the Bible (which aims to present just the J source, which, according to Friedman, also extends beyond the Pentateuch into parts of the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings).

Having spent a lot of time with Friedman’s and other scholars’ work (and having indulged in a lengthy detour into the related topic of the Sea Peoples), I have come to a somewhat different view of the real Exodus and its aftermath. In some ways, it’s closer to a straightforward reading of the Bible (or at least the J source, which is generally regarded as the oldest one); in other ways, it’s weirder. Here (and in part 2) I’ll present my best-guess historical scenario, covering roughly the two millennia from Abraham to Alexander.

The Age of Amorites

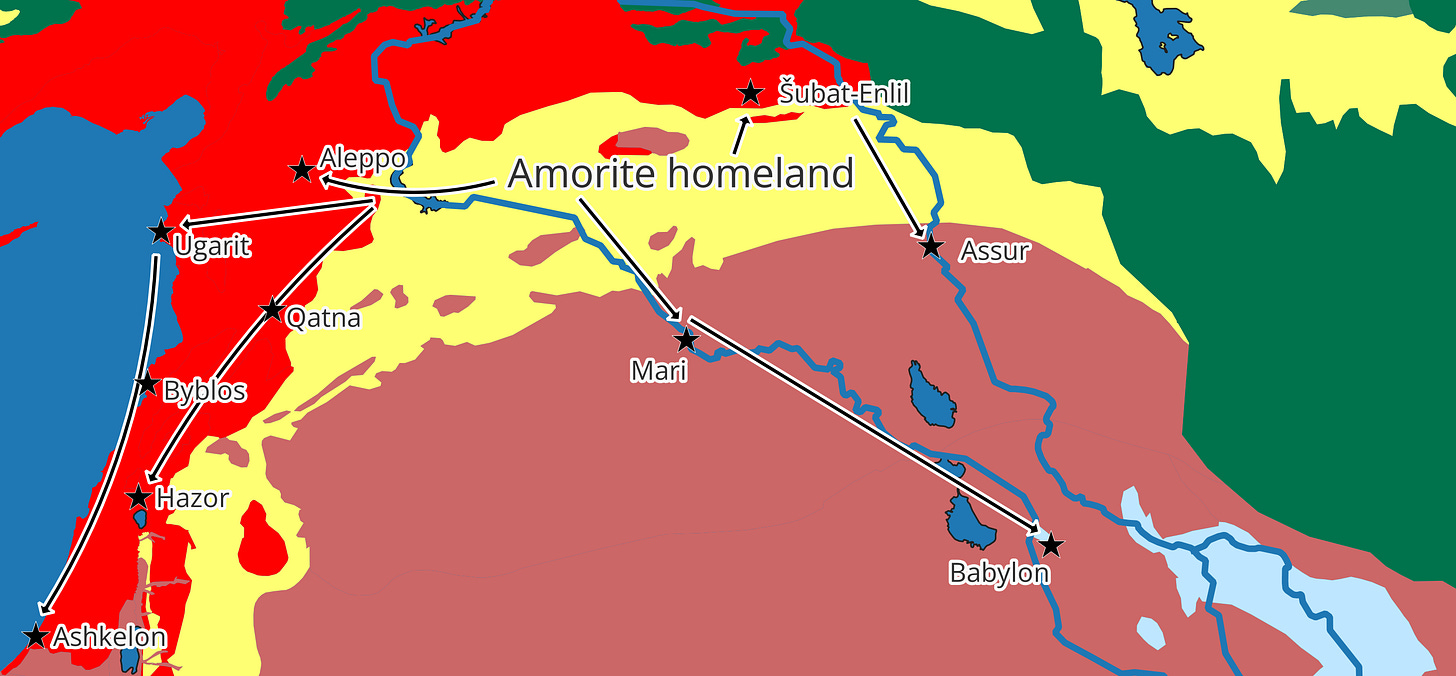

The story of the Bible is a story of the Northwest Semitic ethnolinguistic group, which crystallized around 2450 BCE,1 when it parted ways with the ancestors of, among others, the speakers of Proto-Arabic. The Proto–Northwest Semites were scattered throughout the Eastern Mediterranean ecoregion but also occupied the adjacent Syrian xeric grasslands (aka the Middle East steppe), where a subgroup herded sheep and goats and bred the prestigious ass hybrids called kungas. But when the climate turned dramatically drier around 2200 BCE, this lifestyle became untenable, driving many of the pastoralists to become “mercenaries and merchants”2 who led and guarded donkey caravans. Sumerians3 referred to these people as something like “Amurru,” basically meaning “westerners,” and the name stuck: they are remembered as the Amorites.

The details aren’t well understood, but, gradually, various Amorite strongmen established enclaves and took power all over the place. The upshot was that, in the words of Aaron Burke, “By the end of the nineteenth century [BC], Amorite dynasties were established across the breadth of the Fertile Crescent to such an extent that the ensuing late [Middle Bronze Age] (ca. 1800–1550 BC) can arguably be identified as the ‘Age of Amorites.’”4

As the map above indicates, one of the areas of Amorite dominance was the Levantine coast, a key node in the trade network of Egypt. The Amorite rulers of Byblos (in present-day Lebanon) developed an especially close relationship with the Egyptian elite, adopting Egyptian styles5 and collaborating on a complex joint venture in which Byblos supplied cedar lumber to build ships6 to transport turquoise out of an Egyptian-controlled mine in the Sinai Peninsula.7 In fact, I think that it was scribes working for the Byblian state, c. 1850 BCE,8 who adapted Egyptian hieroglyphs for use with the Amorites’ Northwest Semitic language, creating both a dead-end syllabic script (which remains undeciphered) and, more consequentially, the alphabet.9 (I have a separate post outlining where the alphabet went from there.)

Pharaoh and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Coat

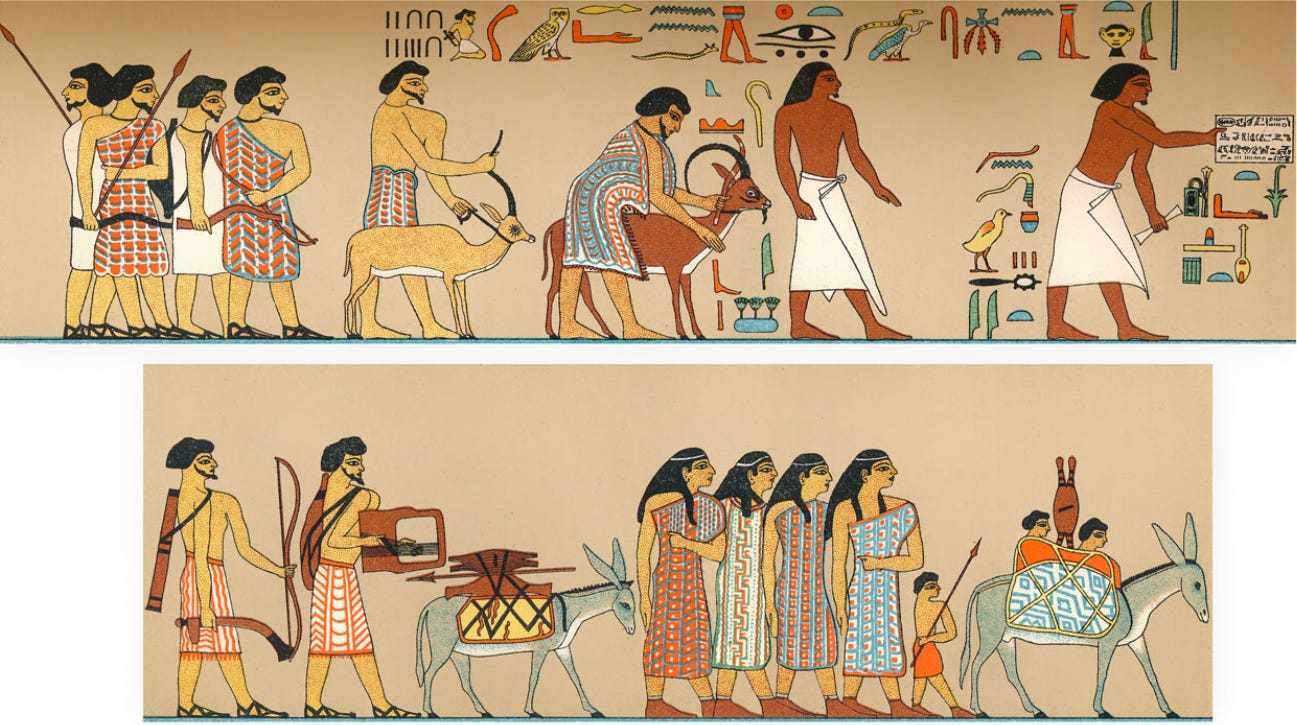

Amorites became a large part of the population in one particular place in the eastern Nile Delta, a city called Hut-waret by the Egyptians but now remembered as Avaris: “a cosmopolitan harbour town with a large Levantine community involved in trade, sea travel and boat production.”10 Egyptians referred to Amorites as “Aamu” (conventionally translated into English as “Asiatics”), possibly derived from the Amorite word for “people” (or even the word “Amurru”/Amorite itself, but probably not).11

Egyptian visual representations of the Amorites featured unusual clothing: Amorite men wore “multi-coloured, detailed” kilts and other garments, while Amorite women sported dresses that were likewise “often detailed with red, blue and white designs,” sometimes accessorized with boots that “appear[ed] to be painted yellow or red.”12

Around 1710 BCE,13 under unknown circumstances, the power of the Egyptian state broke down, and an Amorite — perhaps a local bigwig in Avaris — set himself up as ruler of the Nile Delta, founding the 15th Dynasty. Outside the Delta, rival (non-Amorite) pharaohs sprang up. Egypt would eventually be reunified under a single pharaoh, but it would take around 140 years.

During that time (known as the Second Intermediate Period), around 1610 BCE,14 a man in Egypt purchased a 17-year-old15 slave from the southern Levant. Surprisingly, the slave ended up rising through the ranks of Egyptian society, eventually working for the Pharaoh himself (Apepi, if I had to guess). The slave’s name was Joseph, whose “coat of many colors” may have been a memento of Egypto-Amorite court fashion16 (and not a gift from his father, as later stories claimed). But Joseph himself was not an Amorite. So what was he?

“Blessed Is Abram to El the Highest”

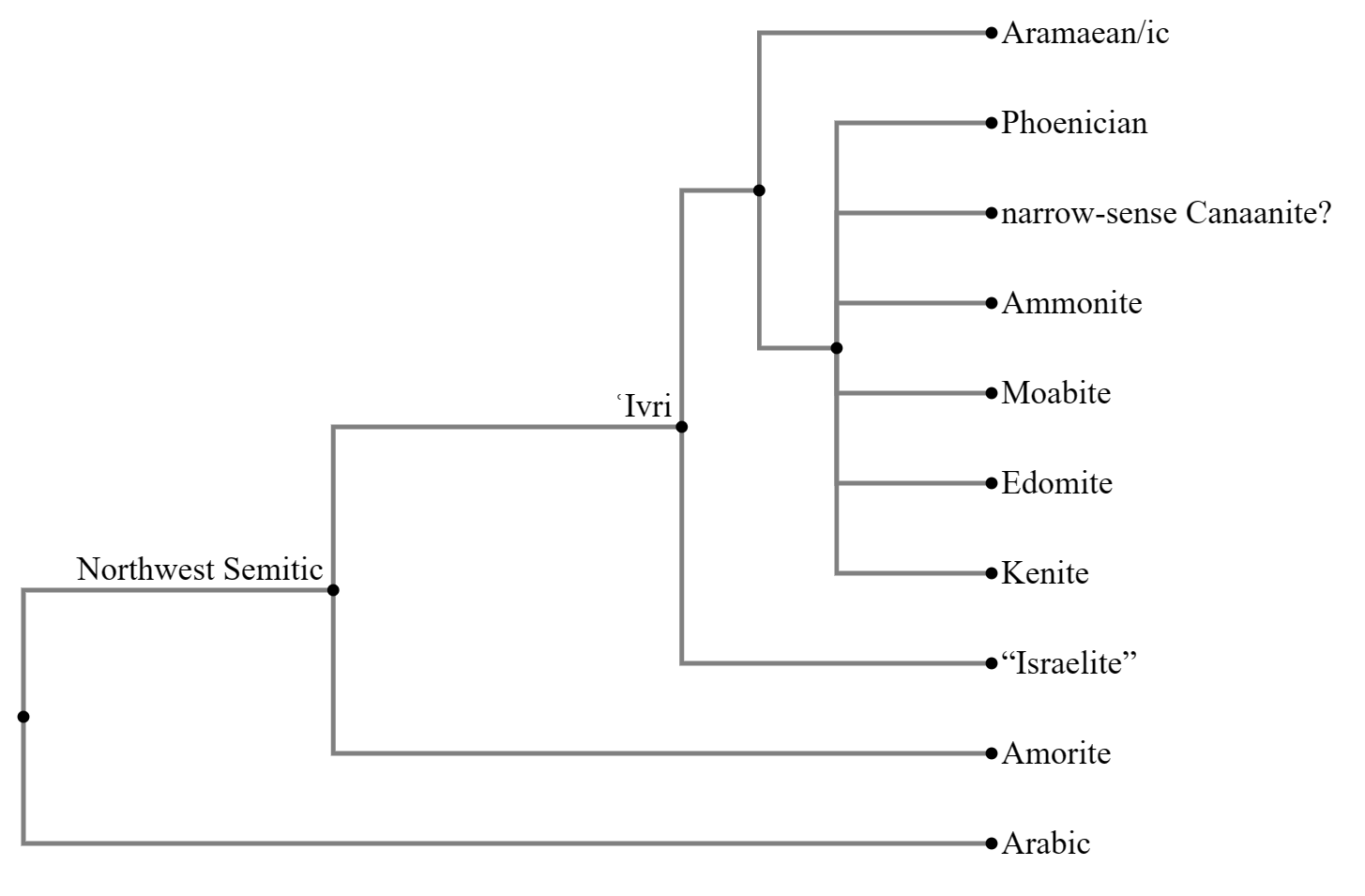

The Amorites constituted just one of the branches of the Northwest Semitic “family”; I’ll refer to the other main branch as the ʿIvri people or ʿIvrim. While Amorite elites vied for geopolitical power, their ʿIvri cousins farmed and herded in the usual unglamorous way, speaking closely related dialects throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. Only later, around 1500 BCE, did regional differences harden enough to create distinct Aramaic (north) and Canaanite (south) language groups within the ʿIvri clade.17

The life of “Abram the ʿIvri” (Genesis 14:13 (J18)) illustrates the earlier fluidity. Born in ~1780 BCE,19 he grew up in Haran,20 at the far northern end of the Eastern Mediterranean in present-day Turkey, but meandered all the way to Hebron in present-day Israel/Palestine, where he “tent[ed] among the oaks of Mamre the Amorite” (Genesis 14:13 (J)).21 Abram’s one brush with fame came around 1760 BCE. At that time, Elam, a polity centered in southwestern Iran, exerted influence over a wide area. When faced with rebellion from its vassals in the vicinity of the Dead Sea (ruling over the cities of Sodom, Gomorrah, Adamah, Zeboiim, and Bela), Elam dispatched a coalition of other vassal kings to inflict punishment.22 In a raid on Sodom, they took property and captives, including Lot, Abram’s nephew, who lived there. But Abram and his Amorite buddies chased after the raiders and managed to get back what was taken. The king of Sodom thanked Abram personally, and King Melchizedek of Salem (aka Jerusalem23), a “priest of El the Highest,” supplied bread, wine, and a blessing:24

Blessed is Abram to El the Highest, creator of skies and earth. And blessed is El the Highest, who delivered your foes into your hand. (Genesis 14:19-20 (J))25

El was a Northwest Semitic god, worshipped by Amorites and ʿIvrim alike. (“El” could also simply mean “god” in a generic sense.) El was regarded as the father of various other gods, including the storm god Baʿal Haddu (“Baʿal” just meant “lord”) and Jeru/salem’s namesake, Šalem. And El had a consort, named Asherah, though I prefer to think of her as Mrs. God.

The Rise and Fall of the House of Israel

Abram begat Isaac, who begat Israel,26 who begat, among other sons, Joseph, who was taken by Arab27 traders on their way to Egypt and sold into slavery, alongside other, more valuable commodities (like botanical gums from Gilead28). Somehow,29 though, Joseph gained the favor of the Amorite pharaoh. It probably helped that they had similar ethnolinguistic backgrounds: the Amorite and ʿIvri languages had parted ways only ~450 years before,30 in the same ballpark as the divergence between, say, present-day Spanish and Portuguese, which are almost mutually intelligible.31

Joseph shared his good fortune, inviting his shepherd brothers and other relatives to bring their families and livestock to the outskirts of the Egypto-Amorite capital of Avaris. Some 70 households made the trip.32

For a little while, life was good. The ʿIvri population in Egypt grew. Despite close ties with Egyptian society, Joseph’s kinsmen preserved their sense of distinctiveness, taking pride in their descent from salt-of-the-earth Israel. They continued to worship El, not the gods of Egypt. (“Israel” (yisraʾel) was, in fact, a theophoric name, probably meaning “El protected.”33)

The good times didn’t last long. “Joseph died, and all his brothers, and all that generation…A new king arose over Egypt who did not know Joseph” (Exodus 1:6, 8 (J)). Worse than a new king, it was a whole new dynasty:34 around 1570 BCE, the Amorite ruling family was toppled by the “indigenous” Ahmose I, who put the pieces of Egypt back together under unified rule. Not just in Egypt but throughout the Near East, the Age of Amorites was coming to a close.

Later pharaonic propaganda reminded Egyptians that it was Ahmose’s dynasty that had brought an end to the dark time when “Asiatics [= Amorites] were in the midst of the Delta (at) Avaris, while nomads in their midst were destroying what had been made.” As Danielle Candelora has pointed out, “A careful reading of this passage suggests that it was not the Asiatic population of Avaris, but specifically the nomads in their midst who were remembered later as destructive.”35 Perhaps Joseph and his hick relatives really rubbed the sophisticates of Egypt the wrong way. (As Joseph himself warned his brothers, “all shepherds are abhorrent to Egyptians” (Genesis 46:34 (J)).)

With their royal connections now worthless, the Children of Israel lost their special status and were put to work by the state. They would remain in Egypt, doing menial labor, for about 400 years.36 The Bible contains almost no details about this long period, aside from the (plausible) claim that the Children of Israel worked on building the cities of Pithom and Pi-Ramesses, in the same broad region of the eastern Nile Delta where they had lived under Amorite rule.37 What’s clear is that the Children of Israel continued to stand apart, preserving the language and stories of their ʿIvri ancestors. They did, however, borrow at least a handful of Egyptian words at this early stage, including words for “ship,” “ebony,” “hand-span” (a unit of measure), “ink,” and “a rush or reed plant.”38

The Princess of Egypt and Her Wayward Son

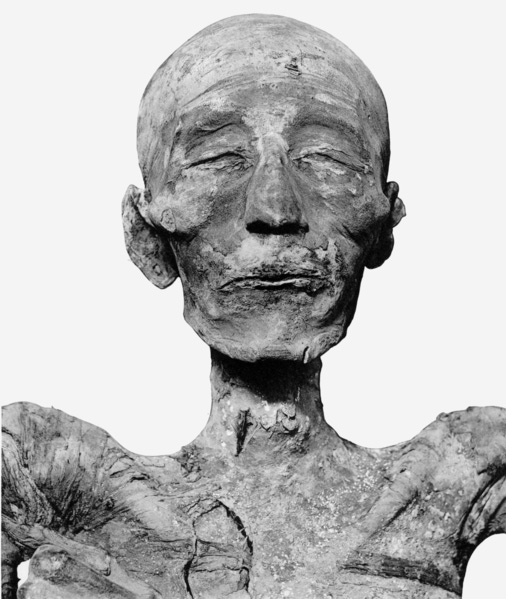

Ramesses II acceded to the throne in ~1296 BCE.39 As Toby Wilkinson points out, he’s the one and only pharaoh who’s been “accorded the epithet ‘the Great’ by modern Egyptologists.”40 One thing that was great about him was his complement of offspring: he “sired at least forty-five sons and more than fifty daughters. Surviving records are incomplete, so he likely fathered more than a hundred” children in total.41

One of his many daughters gave birth to a son: Moses. “Moses” (or rather, in its original form, something like Ma-see) seems to be an authentically Egyptian name, as has been noted by, among others, the Egyptologist Donald Redford:

…the [personal name] “Moses” (Hebrew Mōše[h]) enjoys excellent credentials as an Egyptian name…The verbal affix -mose…turns up in such well-known names as Thutmose, Amenmose, and Ptahmose...42

Taken literally, such a name meant something like “[Thoth/Amun/Ptah/other god] is born,” from the Egyptian root mśy, “to be born.” But an abbreviated version using just the “Mose” part was perfectly normal. For instance, a recent study of New Kingdom tombs from Memphis identified three different people named Mose, including a steward and a scribe.

The story that Moses was actually an ʿIvri child from the Children of Israel whom the pharaoh’s daughter just happened to discover “among the reeds by the bank of the Nile” (Exodus 2:3 (E)) was a later invention, designed to downplay Moses’ Egyptianness. But I’m tempted to believe that Moses really was raised by an ʿIvri wet-nurse, as described in Exodus 2:7-10 (E), which may have given him a lifelong soft spot for the ʿIvrim. (I would say that Freud would have a field day, but, though Freud actually did write a book about Moses (contending, like me, that he was actually Egyptian), Freud doesn’t seem to have pondered the wet-nurse psychology — an uncharacteristic oversight!)

Moses grew up and quickly got himself in trouble. One day, having come upon an Egyptian man beating an ʿIvri laborer, Moses “turned this way and that and, seeing no one about, he struck down the Egyptian and hid him in the sand” (Exodus 2:12 (J)). He thought he had gotten away with the murder, but he was wrong. “When Pharaoh learned of the matter, he sought to kill Moses” — so Moses decided to run away. He headed to “the land of Midian” (Exodus 2:15 (J)).

The Land of Midian

It wasn’t easy to escape the pharaoh’s grasp. Even far south along the Nile, the land of Kush was under Egypt’s imperial control; so too was much of the Eastern Mediterranean, including the province of Canaan, administered from the city of Gaza. The harsh deserts of the Sinai Peninsula were less well surveilled but were dangerous in their own way for the inexperienced traveler.

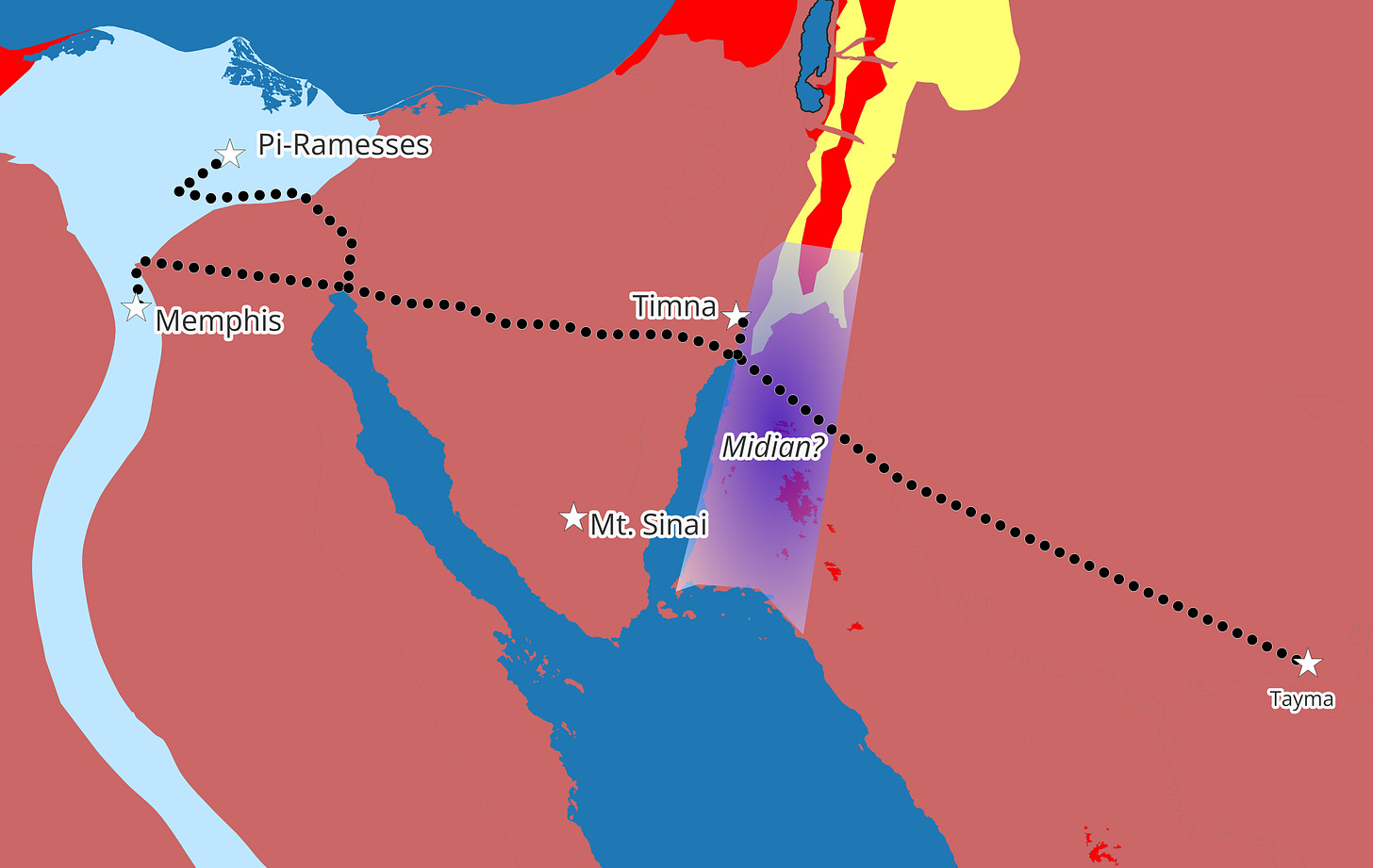

Recently, though — under Ramesses II, if not a bit earlier43 — the Egyptian state had blazed a trail far east to the copper-rich Timna Valley, south of the Dead Sea on the edge of northwest Arabia (in or near the region that the Bible calls Midian44). A series of later Ramesside rock inscriptions marked the official route for such mining and trading expeditions, going from the Nile Delta across the Sinai to Timna and beyond:

At least by the time of Ramesses III, nervous Egyptian travelers departing on this route from the vicinity of Memphis could feel reassured by “a prophylactic statue of the king, represented alongside the goddess Hathor”:

According to the formulae inscribed on the statue, the [statue] was intended to protect the travellers against snakebites and scorpion stings. The presence of such a monument at the entrance of a desert trail is not surprising, for we know that a “remover of scorpions” had sometimes accompanied that kind of expedition…and that Hathor protected mining expeditions to the deserts in general and in Sinai in particular.45

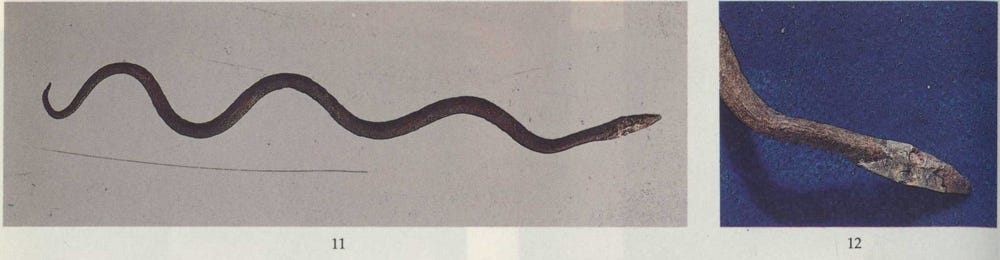

Hathor also appeared all the way at the other end of this ancient desert trail, in Timna, where Egyptians created a modest “chapel” or “kiosk” for the goddess, complete with a statue of her. In the vicinity of the chapel, archaeologists discovered a “small, beautiful” bronze snake, probably a votive offering (perhaps also reflecting worries about snakebites):46

Interestingly, the Egyptian chapel in Timna stood right next to a pre-existing shrine that had been built by local nomads and included an altar, basins for blood and water, and standing stones. The archaeologist Uzi Avner has argued that this sanctuary-sharing was one of several indications that, in this setting, Egypt relied more on cooperation than coercion:

An agreement with the local population was essential. The presumed interest of the Egyptians in such an agreement with the local population finds support in their general policy in Canaan; namely, minimal friction and focusing on securing the main international roads.

…The agreement could have worked as follows: Before each mining season (winter) Egyptian officials met with the chiefs of the desert tribes to negotiate the amount of copper to be produced by the locals for the Egyptians during the season. Whatever the locals produced beyond the agreed amount was their own profit.…Following the signing of the agreement, the Egyptians sent expeditions…similar to those described on the stelae of Serabit al-Khadem [the turquoise mine in the Sinai Peninsula], including several high officials, scribes and others, and an army unit.47

When Moses ran away from Egypt, I speculate that he took along with him a personal bodyguard, Hur,48 who, I speculate further, had served in the Egyptian army and may even have gone on mining expeditions to Timna. At any rate, lacking a better option, Moses (and Hur?) headed eastward across the Sinai, toward Timna and the land of Midian, away from the direct authority of the pharaoh.

But who were the people who called these eastern lands home? They were an obscure bunch, but they came to be associated with a notorious legendary ancestor: the world’s first murderer, Cain.

The Children of Cain

Let’s review the Northwest Semitic family tree and fill in some gaps:

Around 2050 BCE, the proto-Northwest Semites begat the Amorites and the ʿIvrim. Around 1600 BCE, one group of ʿIvrim — Joseph and his relatives, the Children of Israel — left the Levant and went to Egypt, where they remained for 400 years. Back in the Levant, though, life went on. Around 1500 BCE, the difference between the northern ʿIvrim and the southern ʿIvrim became stark enough to beget distinct Aramaic and “Canaanite” languages.

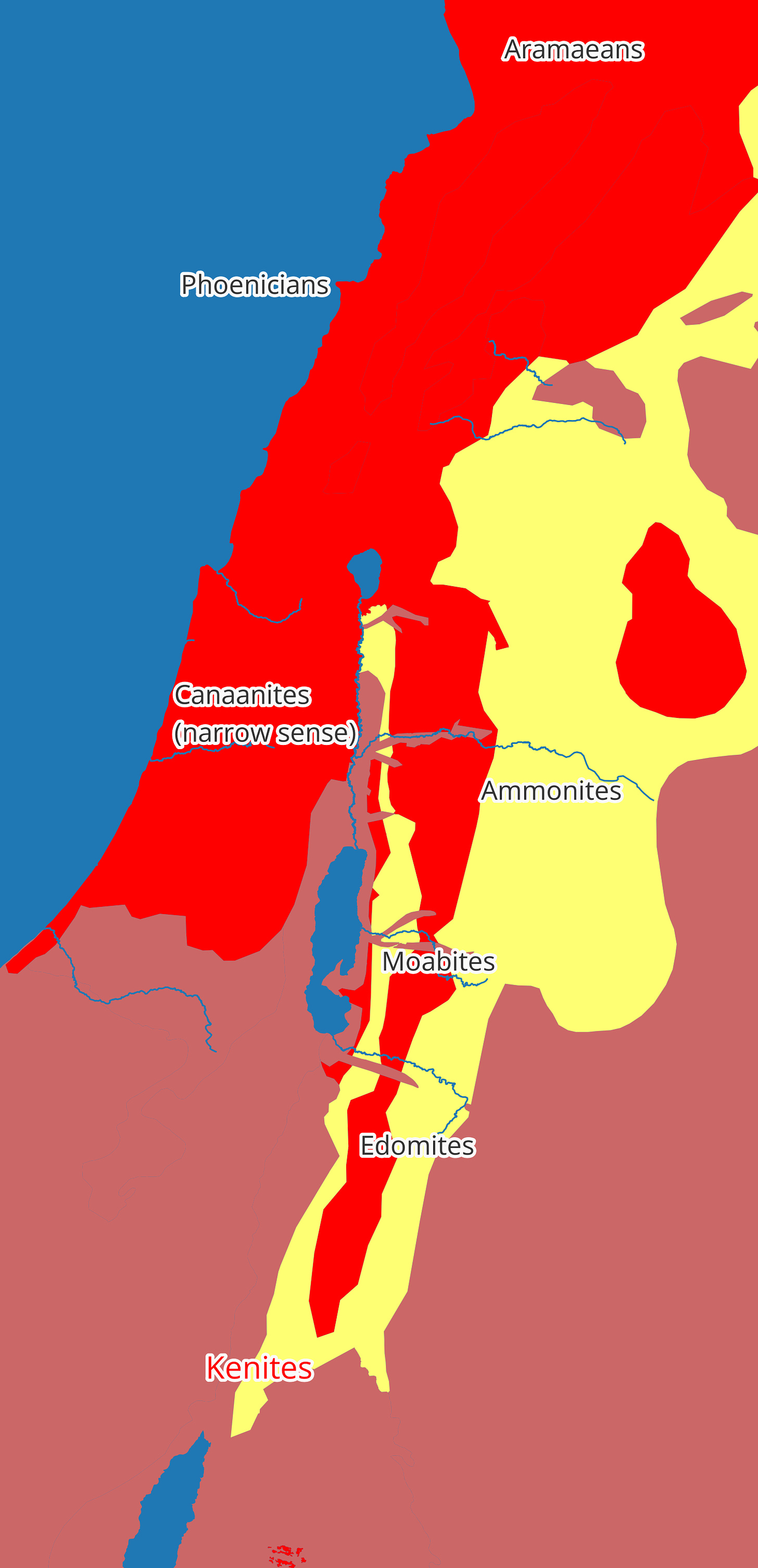

Unfortunately, the term “Canaanite,” like most such designations in the ancient world, is vague. In the broad sense, Canaan could include a large chunk of the Eastern Mediterranean; in the narrow sense, it was confined to just the area west of the Jordan River and Dead Sea with a Mediterranean-forest biome. As time passed, the Canaanites (in the broad sense) differentiated into smaller groups with somewhat different dialects and cultures, including Phoenicians along the northern coast, Canaanites (in the narrow sense) in the “Cis-Jordan,” and several regional clusters to the east in the “Trans-Jordan”: Ammonites, Moabites, Edomites, and — I propose — Kenites in the far south, around Timna and the Gulf of Aqaba. “Kenites” is the usual English rendering of a Biblical Hebrew word that can be transliterated as qeni,49 but the Bible also refers to the same group with the collective singular name qayin — exactly the same as the name of the guy who slew Abel.50

The red areas in the map above represent ecoregions with Mediterranean-forest biomes; yellow, grasslands; and unpleasant dark pink, deserts. (I’m following the official color scheme!) So one can understand why the nomadic Kenites, relegated to harsher environments than their Canaanite brethren, felt cursed — but also took pride in their toughness and adaptability (Genesis 4:10-15, 4:19-22 (J)):

…YHWH said, “What have you done? Hark, your brother’s blood cries out to Me from the ground! Therefore, you shall be more cursed than the ground, which opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. If you till the soil, it shall no longer yield its strength to you. You shall become a ceaseless wanderer on earth.”

Cain said to YHWH, “My punishment is too great to bear! Since You have banished me this day from the soil, and I must avoid Your presence and become a restless wanderer on earth—anyone who meets me may kill me!”

YHWH said to him, “I promise, if anyone kills Cain, sevenfold vengeance shall be taken on him.”51…

[Cain’s descendant] Lamech took to himself two wives: the name of the one was Adah, and the name of the other was Zillah.

Adah bore Jabal; he was the ancestor of those who dwell in tents and amidst herds.

And the name of his brother was Jubal; he was the ancestor of all who play the lyre and the pipe.

As for Zillah, she bore Tubal-cain, who forged all implements of copper and iron.

…And Lamech said to his wives… “If Cain is avenged sevenfold, / Then Lamech seventy-sevenfold.”

The link between metal-working (“Tubal-cain, who forged all implements of copper…”) and an ancestor named “Cain” is probably something of a pun: as John Day has noted, “The name [qayin] is most naturally to be seen as cognate with Arabic qayn as well as Aramaic qyny’, [meaning] ‘smith.’”52 It was these wandering tent-dwellers, some of whom collaborated with Egypt on copper-mining in the Timna Valley, whom Moses (and Hur?) encountered at the edge of the land of Midian. And it was love at first sight (Exodus 2:15-21 (J)):

[Moses] arrived in the land of Midian, and sat down beside a well.

Now the priest of Midian had seven daughters. They came to draw water, and filled the troughs to water their father’s flock; but shepherds came and drove them off. Moses rose to their defense, and he watered their flock.

When they returned to their father Reuel, he said, “How is it that you have come back so soon today?”

They answered, “An Egyptian rescued us from the shepherds; he even drew water for us and watered the flock.”

He said to his daughters, “Where is he then? Why did you leave the man? Ask him in to break bread.”

Moses consented to stay with the man, and he gave Moses his daughter Zipporah as wife.

So Moses married into the family of Reuel,53 “priest of Midian,” who was a Kenite,54 part of the broader Canaanite and even broader ʿIvri families.

But the term “Kenite” might be an anachronism here. Under Ramesses II, the Egyptian/nomad copper operation was still new. It was only later, closer to 1000 BCE,55 that Timna mining output hit its peak; at this much earlier stage, would the people involved have already acquired an ethnonym meaning something like “the smiths”?56 But if the Kenites were not yet called “Kenites” when Moses met them, what were they called? And what god was Reuel a priest of?

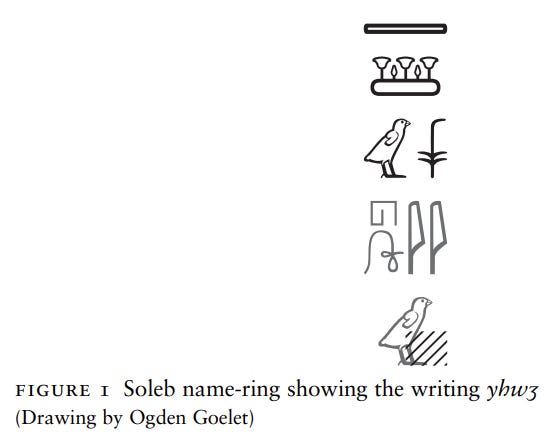

(The) Yahwa

Egypt had a long history of imperial activity in the Levant, and, though it had the most dealings with the settled people of narrow-sense Canaan, it also crossed paths with what it called “Shasu,” derived from an Egyptian word meaning “to wander”: nomads.57 There were many little subtypes of Shasu in different regions, each with its own group identity and tribal name. An Egyptian inscription dating from nearly a century before the reign of Ramesses II preserved some of these tribal names (albeit in hieroglyphic writing that didn’t explicitly represent vowels): there were the Trbr, the Smt, the Pyspys, and — drumroll — the Yhwꜣ, probably pronounced “Yahwa.”58 (The last letter there, ꜣ, is “Egyptological alef,” also written as ȝ.)

As Daniel Fleming says in his recent book, this is “the oldest evidence by far for the name Yahweh, albeit in a form still not clearly identified with the deity.” The same Yhwꜣ also appears in a Ramesses II–era variant of the same list of tribal names, seemingly under the heading of “Seir,”59 referring to a mountain and/or territory south of Edom — the same rough area labeled as Kenite in my map above. Fleming emphasizes that, in these Egyptian texts, Yhwꜣ seems to identify a group or a people, not a god; if we didn’t already know that “Yahweh” was regarded as a divine name, we wouldn’t assume that the Yhwꜣ of the inscriptions was. So I think that, before the Kenites were the Kenites, around 1400 BCE till at least 1200 BCE, they were the Yahwa.

How did “Yahwa” go from the name of a group to the name of a god? I can only guess. Like other broad-sense Canaanites, the Yahwa probably started out worshipping El and other members of the Northwest Semitic pantheon, but then something changed. The best analogue I know of is Ashur/Assur, the first Assyrian capital city but also the Assyrian chief deity. The East Semitic-speaking Assyrians were only distantly related to the Northwest Semitic-speaking Yahwa, having diverged some 2,500 years before the time of Moses, so I doubt that there was direct influence. But much of what Stefan M. Maul says in his 2017 overview of Assyrian religion maps well onto Yahwism:

Even the name of the most Assyrian of all gods escapes our understanding. We cannot etymologize it, and we do not know whether Assur (Aššur) bears the name of his city or the city the name of its god.

…Unlike all of the other great gods of the ancient Near East, Assur was originally an independent and solitary god who was conceived as entirely without family and without involvement in divine communities and hierarchies. For him, neither father nor mother is envisioned, nor does he have a wife and children.

…His character is difficult to capture. He is the city and its power; no further attributes can be identified.

…Assur is called “the maker of (all) the creatures of heaven and earth, fashioner of the mountains”, but aside from this reference to his role as a primeval god of creation, allusions to more specific deeds are missing. Assur appears without attributes, he is simply god. So it is not surprising that, particularly in the Old Assyrian period, he is often mentioned not with his name but rather is just called ilum “god.” Somewhat ironically, it was exactly this absence of any particular character traits that permitted the unprecedented rise of Assur, for it allowed the recognition of an all‐encompassing divinity in him, which could easily absorb deities venerated in other regions.

Assur was the deified personification of a city, and Yahwa was the deified personification of a tribe of nomads — the tribe that welcomed the pharaoh’s grandson, who quickly went native. With the zeal of a convert, he became more Yahwa than the Yahwa.

Yahwa, God of the ʿIvrim?

Moses realized that, despite their differences, the Yahwa and the Children of Israel back in Egypt and the narrow-sense Canaanites living in the Egyptian province of Canaan all had a lot in common; they were all ʿIvrim or, as it’s usually translated, Hebrews. (Subtle differences in their languages would have been lost on Moses, who grew up speaking Egyptian and only learned the broad-sense Canaanite language, probably badly, as an adult.) Maybe Yahwa was the god and protector not just of the Yahwa nomads but of all ʿIvrim.

As long as Moses still faced a murder rap in Egypt, such thoughts were idle musings. But then, “a long time after [Moses settled down with Zipporah]…the king of Egypt died” (Exodus 2:23 (J)). Thus, around 1230 BCE,60 Ramesses II was succeeded by his thirteenth son, Merenptah, not a young man at over 60 years old; the three previous crown princes had all died before reaching the throne.61 It was then that Moses began to hear the voice of Yahwa, telling him, “Go back to Egypt, for all the men who sought to kill you are dead” (Exodus 4:19 (J)). With a new pharaoh in place, Moses expected to get away with murder.

But he also had grander visions. The peculiarity of the famous burning-bush image strikes me as genuine, so I’d guess that Moses really did experience divine hallucinations. He thought that Yahwa wanted him to liberate the ʿIvrim of Egypt and take them to live among their kinsmen in Canaan:

[YHWH said,] “I have come down to rescue them from the Egyptians and to bring them out of that land to a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk62 and honey…” (Exodus 3:8 (J))

But how could this be done, with the might of the Egyptian state set against it? Moses’ audacious plan (received, he said, from Yahwa) was to employ treachery:

“…[Y]ou shall go with the elders of Israel to the king of Egypt and you shall say to him, ‘YHWH, the God of the Hebrews, manifested Himself to us. Now therefore, let us go a distance of three days into the wilderness to sacrifice to YHWH our God.’” (Genesis 3:18 (J))

(In the Bible, the phrase “God of the ʿIvrim” [ʾelohei haʿivriyyim] only appears in the early part of Exodus.63 Pan-ʿIvricanism was a concept that mattered a lot to Moses but later lost salience.)

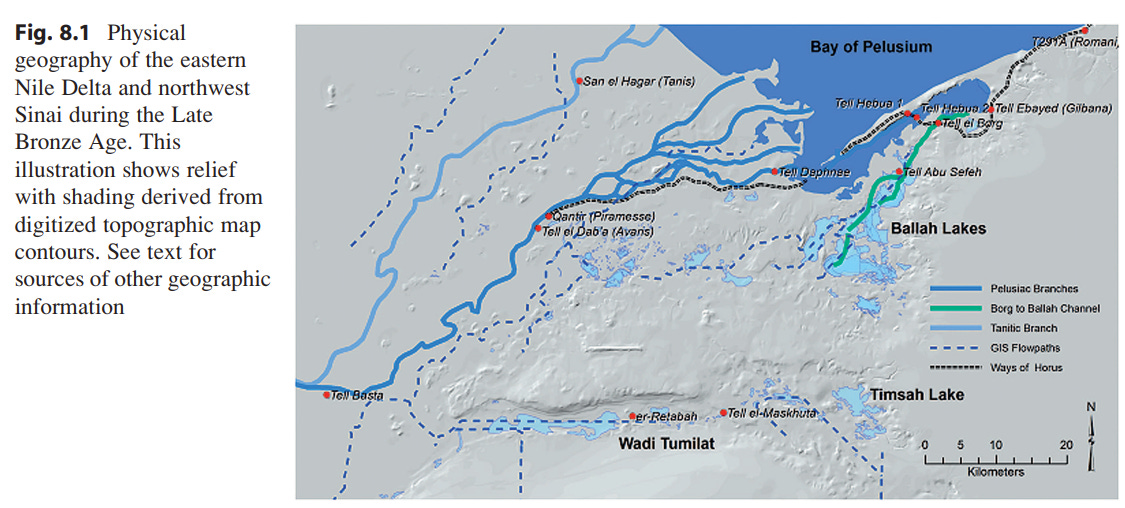

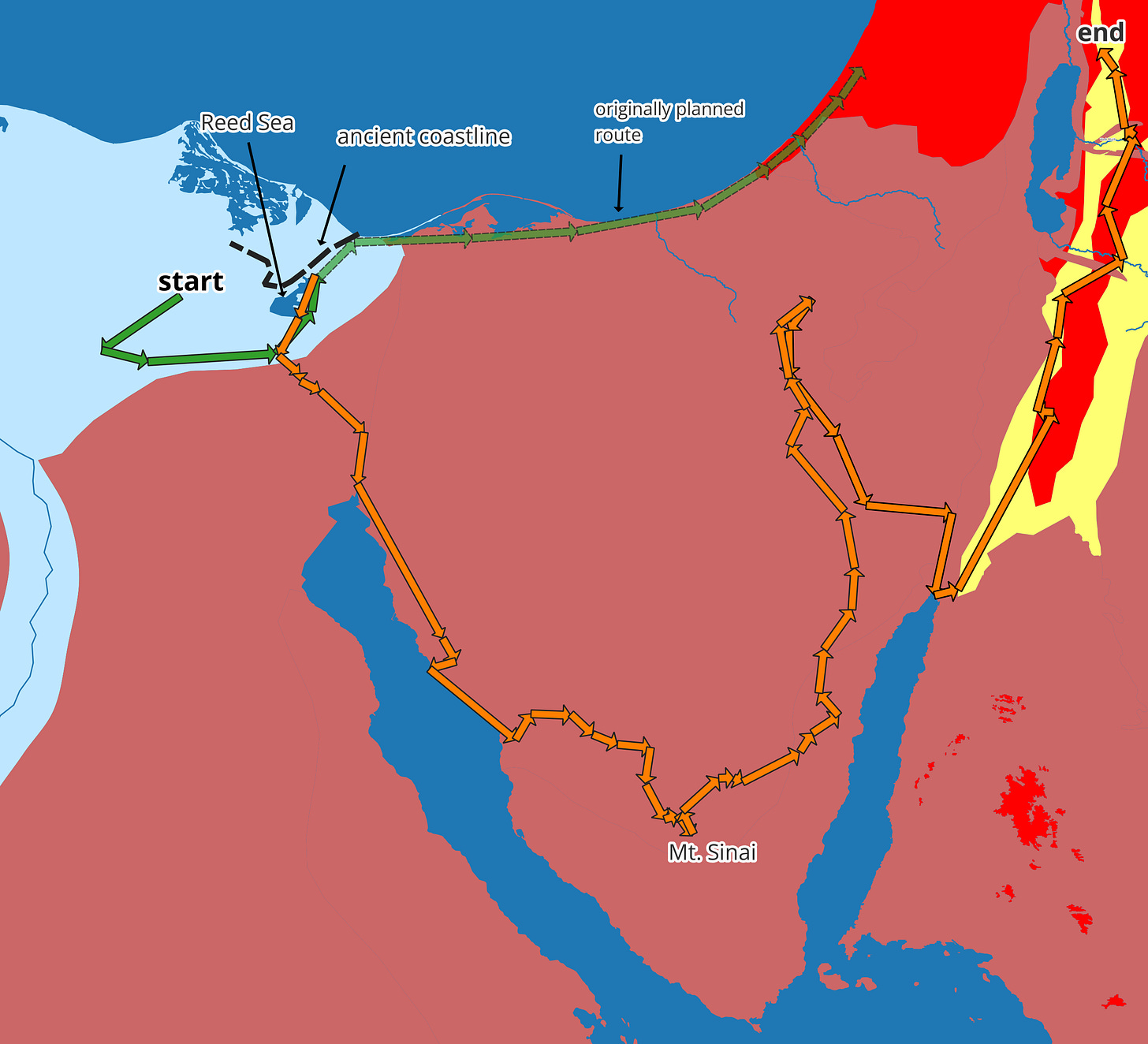

Since the Egyptians wanted to maintain good relations with the eastern nomads who helped keep the copper flowing, it was not crazy to think that they would grant this request for a modest ʿIvri pilgrimage. But then, instead of actually taking a quick trip to the desert and back, Moses and the Children of Israel would — so the plant went — suddenly veer north, toward the Mediterranean coast. After sneaking past a series of forts, they would take the Way of Horus — the most important road in and out of Egypt — all the way to Canaan.64 (Moses may have intended to rely on his Egyptian bodyguard, Hur, for navigation.) With the blood of pharaohs flowing through his veins and the voice of the god of the ʿIvrim resounding in his head, Moses was confident it would all work out.

I’m Putting Together a Team…

The biblical account is oddly unclear about who accompanied Moses on his journey back to Egypt, with multiple characters popping up in the middle of (different versions of) the story without ever getting proper introductions — and then disappearing just as mysteriously. But I think it was a small crew. He brought his wife, Zipporah, and his two young sons, Gershom and Eliezer,65 “mounted…on an ass” (Exodus 4:20 (J)). I think he also brought Hur, though the Bible doesn’t actually say so. This little quintet — Moses, Zipporah, Gershom, Eliezer, and Hur — might have traveled amidst a larger group of Yahwa pastoralists, including Reuel’s son (and thus Moses’ brother-in-law) Hobab,66 who were just going to Egypt to water their flocks, not to liberate the Children of Israel. This may have been part of the compensation in the tribal copper deal: access to scarce water. There’s actually direct evidence of Shasu groups being allowed to use Egyptian water in exactly this period, in a letter written by an Egyptian official to his boss during the reign of Merenptah:

We have finished passing the tribes of the Shasu of Edom through the Fortress of Merneptah-Hotephirma, L.P.H. in Theku, to the pools of Pithom…in order to sustain them and their herds in the domain of Pharaoh…67

But, if Hobab & co. were just there for the water and weren’t planning to help Moses free the Children of Israel, then there was a problem: Moses wasn’t fluent in ʿIvri. How could he convince “the elders of Israel” to follow him if he could speak to them only clumsily? I think this is the historical reality behind the claim that Moses was “slow of speech and slow of tongue” (Exodus 4:10 (J)). He didn’t have a speech impediment; he just needed ʿIvri as a Second Language classes.

Luckily for him, Moses managed to recruit two other Yahwa travelers on the way: Aaron and his sister Miriam, “the prophetess” (Exodus 15:20 (J)). (A later retcon, perpetrated by Aaron’s descendants — don’t worry; we’ll get there — would claim that Aaron and Miriam were Moses’ siblings, but they weren’t.68) It’s unclear how exactly he found them. The story just says:

YHWH said to Aaron, “Go to meet Moses in the wilderness.” He went and met him at the mountain of God, and he kissed him. Moses told Aaron about all the things that YHWH had committed to him… (Exodus 4:27-28 (J))

“The mountain of God” is usually interpreted as Mt. Sinai, but the text doesn’t actually say this, and I don’t think it makes sense narratively or logistically.69 Instead, “the mountain of God” here probably refers to somewhere in the Eilat Mountains, adjacent to the Timna Valley and more or less on the way from the “Kenite” zone to Egypt along the road shown above. Presumably this “mountain of God” was considered sacred to Yahwa, though it was later superseded within the Moses cult by the more important Mt. Sinai.

Anyway, Moses must have been quite charismatic. Aaron (and apparently Miriam) agreed to be part of his mad scheme. Aaron’s main job was to translate Moses’ broken ʿIvri:

YHWH…said, “…You [Moses] shall speak to him [Aaron] and put the words in his mouth…and he shall speak for you to the people. Thus he shall serve as your spokesman, with you playing the role of God to him.” (Exodus 4:15-16 (J))

Moses’ core team was now assembled: two lieutenants (Aaron the translator and Hur the bodyguard) and some (almost entirely overlooked) women and children (Zipporah, Gershom, Eliezer, and Miriam — and probably also Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu, and his wife, Elisheba70).

A later story, which I don’t think actually happened, clearly aims to show that Aaron and Hur were originally equal in status, notwithstanding Hur’s eventual quasi-erasure. During a battle between the freed Children of Israel and the hated Amalek people,

Moses, Aaron, and Hur went up to the top of [a] hill. Then, whenever Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed; but whenever he let down his hand, Amalek prevailed. But Moses’ hands grew heavy; so they took a stone and put it under him and he sat on it, while Aaron and Hur, one on each side, supported his hands; thus his hands remained steady until the sun set. (Exodus 17:10-12 (E))

There are many artistic depictions of this scene, but my favorite is this one from a Children’s Bible Lessons blog post:

The Not-So-Great Escape, and the Non-Parting of the Non-Red Sea

So Moses and his small band of followers went to Egypt. “Then Moses and Aaron went and assembled all the elders of the Children of Israel. Aaron repeated all the words that YHWH had spoken to Moses…and the people were convinced. When they heard that YHWH had taken note of the Children of Israel and that He had seen their plight, they bowed low in homage” (Exodus 4:29-31 (J)). Again, Moses must have been quite charismatic!

Traditionally, the Children of Israel had worshipped El — it was right there in yisraʾel — but that might not have been much of a barrier. Conceivably, Yahwa himself had evolved out of El, and both were creator gods without much personality. El already had a variety of manifestations and epithets — the Bible includes “El the Highest” and “Helpful El”71 — so it was easy to regard Yahwa as just one more. (The J creation story in Genesis 2 has it both ways and calls him “YHWH God,” YHWH Elohim.)

I have a hard time believing that Moses and Aaron were actually given an audience with Pharaoh Merenptah himself, or that multiple successive plagues forced the recalcitrant pharaoh to give in.72 But, one way or another, “Pharaoh’s taskmasters” (Exodus 5:14 (J)) stood aside to let the Children of Israel and all their “flocks and herds” (Exodus 12:32 (J)) go three days’ journey into the desert to worship Yahwa — and then come back. (In the story, the Egyptians had been suspicious about the request to bring along all the animals — that made it look like an escape attempt, not a short religious pilgrimage! — but Moses pretended that they were necessary for “sacrifices and burnt offerings,” and one couldn’t know which individual animals Yahwa wanted till the last minute (Exodus 10:25 (J)).)

I don’t have a good sense for how large the group of escapees was, but my low-confidence guess is on the order of a thousand people. A “naïve” reading would suggest something ludicrous like two million including women and children — “about six hundred thousand men on foot, aside from children” (Exodus 12:37 (J)); “All the Israelite males, aged twenty years and over…came to 603,550” (Numbers 1:45-6 (P)) — though various efforts at reinterpretation whittle that down to maybe ten thousand.73 My wild guess: the J source originally said “about six hundred men on foot, aside form children,” but later that was viewed as insufficiently impressive, so “thousand” was slipped in, and a few centuries later the P source just went with it.

Anyway, it was time for them to execute the getaway plan. Moses led the Children of Israel right up to “the edge of the wilderness” (Numbers 33:6 (P)), consistent with the permitted pilgrimage route, but then “turn[ed] back” (Exodus 14:2 (P)), away from the desert and toward the road to Canaan. They “encamp[ed] before Pi-hahiroth, between Migdol and the sea, before Baal-zephon” (Exodus 14:1 (P)). Making sense of these obscure place names and prepositional phrases (and how they relate to the rest of the Exodus story) has consumed untold quantities of scholarly life-force over the centuries; here I’ll just skip to what I think is the bottom line, based largely on the work of James K. Hoffmeier and Stephen O. Moshier, who used computer modeling to reconstruct what the Eastern Nile Delta used to look like. Basically, there was a big zone of now vanished lakes (called the Ballah Lakes), and this is what yam suph — traditionally translated as “Red Sea,” but more literally meaning “Reed Sea” — refers to, and broadly where Moses and his followers initially encamped:

But this was a dangerous gamble. To actually make it onto the road to Canaan, the group would have to get past a string of Egyptian fortifications (most of the red dots in the upper right corner of the map above) undetected. But they failed. They were spotted from a distance, and the Egyptian army began to mobilize to stop them — and they had chariots.

Understandably, the Children of Israel, now reversing course in a desperate attempt to evade capture, openly regretted ever having listened to Moses. But then they got lucky: a strong, prolonged wind from the east temporarily exposed portions of the bottom of the Reed Sea, making their escape route more passable. When the wind died down, the water returned to its former position, hindering the Egyptians in their pursuit. The runaways escaped.

The account of this episode in the J source doesn’t actually say that Moses himself parted the sea or even that the sea was parted at all (a later embellishment):

YHWH drove back the sea with a strong east wind all that night, and turned the sea into dry ground. At the morning watch, YHWH looked down upon the Egyptian army from a pillar of fire and cloud, and threw the Egyptian army into panic. He locked the wheels of their chariots so that they moved forward with difficulty. And the Egyptians said, “Let us flee from the Israelites, for YHWH is fighting for them against Egypt.”

At daybreak the sea returned to its normal state, and the Egyptians fled at its approach. But YHWH hurled the Egyptians into the sea. Thus YHWH delivered Israel that day from the Egyptians. Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the shore of the sea. And when Israel saw the wondrous power which YHWH had wielded against the Egyptians, the people feared YHWH; they had faith in YHWH and His servant Moses.74

Could the wind really have done this? It doesn’t seem that implausible. Such things do happen:

Wind setdown occurs in shallow coastal areas when strong winds blow offshore. When wind stress acts for several hours on a body of water, the free water surface acquires a low-angle tilt. This tilt causes the water on the upwind side to recede from the original shoreline, leaving exposed mud flats on the bottom. Wind setdown is opposite to storm surge and comparable in vertical displacement, although wind setdown is less well known because it usually poses no danger to lives and property. Wind setdown events on the order of 2 m were recorded by measuring stations at the western end of Lake Erie on December 1–2, 2006, and January 30–31, 2008. … Cedar Key Harbor in Florida, USA, experienced a 1.0 m drop in water level on September 6, 2004 as Hurricane Frances passed through, then rose to 1.5 m above sea level 9 hours later.75

A British army officer actually observed such an event in Egypt in 1882:

a gale of wind from the eastward set in and became so strong that I had to cease work. Next morning on going out I found that Lake Menzaleh, which is situated on the west side of the [Suez] Canal, had totally disappeared, the effect of the high wind on the shallow water having actually driven it away beyond the horizon, and the natives were walking about on the mud where the day before the fishing-boats, now aground, had been floating.76

So the Children of Israel were out of danger for the time being. But where could they go now? The only option was the desert. The feint had become a reality. Even worse, they couldn’t safely use the straightforward trans-Sinai route that Moses had taken, because Egyptian soldiers and officials might be there. They had to go off the beaten path (though not entirely — the Sinai was crisscrossed with many smaller ancient trails). And the prospect of ever getting to Canaan seemed more remote with each passing day.

Overall, the whole thing was a debacle, but later tradition tried to put a positive spin on it. It was all, of course, part of God’s plan. (In the quotation below, the J source uses the anachronistic term “Way of the Land of the Philistines” — there were no Philistines there yet — to refer to what the Egyptians called the Way of Horus and the Romans would later call the Via Maris.)

Now when Pharaoh let the people go, God did not lead them by way of the land of the Philistines, although it was nearer; for God said, “The people may have a change of heart when they see war, and return to Egypt.” So God led the people round about, by way of the wilderness at the Sea of Reeds. (Exodus 13:17-18 (J77))

What’s Biblical Hebrew for “cope”?

“Israel Is Laid Waste”

From the perspective of the Egyptian state, the fact that a bunch of ʿIvri forced laborers had run off was annoying but not a very big deal. At least they’d been successfully diverted into the desert, where they probably wouldn’t survive for long. Anyway, these ʿIvrim always seemed to be starting trouble for the Empire; little rebellions also kept cropping up in the province of Canaan, but the pharaoh kept putting them down.

Merenptah had bigger fish to fry. In his fifth regnal year — around 1225 BCE — the Libyans in the western desert mounted a large-scale attack, but Merenptah’s forces beat them. He commemorated his victory with an inscribed stele. Toward the end of the text, which was mostly about his defeat of the Libyans, he included a few lines about how various eastern nuisances had also been subdued:78

The princes are prostrate, saying “Mercy!” Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows. Desolation is for Tehenu; Hatti is pacified; Plundered is the Canaan with every evil; Carried off is Ashkelon; seized upon is Gezer; Yanoam is made as that which does not exist; Israel is laid waste; his seed is not; Hurru is become a widow of Egypt! All lands together, they are pacified.

(“The Nine Bows” was a traditional collective term for Egypt’s enemies; “Tehenu” referred to Libyans; “Hatti” referred to the Hittite state; Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yanoam were rebellious cities in Canaan; and “Hurru” was a synonym for Canaan.) This is the earliest known extra-biblical reference to “Israel” (ysrỉꜣr).

One interesting aspect of Egyptian hieroglyphic writing is its use of special symbols called determinatives that indicate what semantic category a word falls under. In the Merenptah Victory Stele, as Patrick Mazani has written,

The word Canaan appears with a determinative that indicates that it is a country. After the mention of Canaan comes Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yanoam, all three appearing with a city determinative. By contrast, the determinative with Israel refers to a people.79

The correct interpretation of this stele is much debated, but I think it aligns with the scenario I’ve been sketching out. To Egypt, “Israel” meant the people I’ve been calling “the Children of Israel.” They didn’t have their own country or city; as the marginalized descendants of ʿIvri migrants from centuries past, they didn’t count as fully Egyptian, but they were nonetheless under Egypt’s authority, like the narrow-sense Canaanites. They tried to resist that authority and paid the price. As far as the Egyptian state knew, that was the end of the story: “Israel is laid waste; his seed is not” (that is, “his” seed is no more). And, at first, it looked much the same way to Israel: “the people grumbled against Moses and said, ‘Why did you bring us up from Egypt, to kill us and our children and livestock with thirst?’” (Exodus 17:3 (J)).

(It’s not too surprising that the Merenptah stele didn’t mention the role of Moses, Aaron, Hur, or the Yahwa (not important), let alone the possible loss of some soldiers to freak weather at the Reed Sea (embarrassing).)

Incidentally, assuming that Moses and his followers fled after the start of Merenptah’s reign but before or during its fifth year, we can use radiocarbon data to pin down the beginning of the Exodus to a 95.4% credible interval of [1241, 1214] BCE — call it 1228 BCE ±13 years.80

Manna and Quail

Of course, for Team Moses and the Children of Israel, the flight from Egypt wasn’t the end of the story. Their main task now was to get out of the desert. They did have some resources — “very much livestock, both flocks and herds,” plus “unleavened cakes of the dough that they had taken out of Egypt” (Exodus 12:38-39 (J)) — but finding enough water would be a constant struggle.

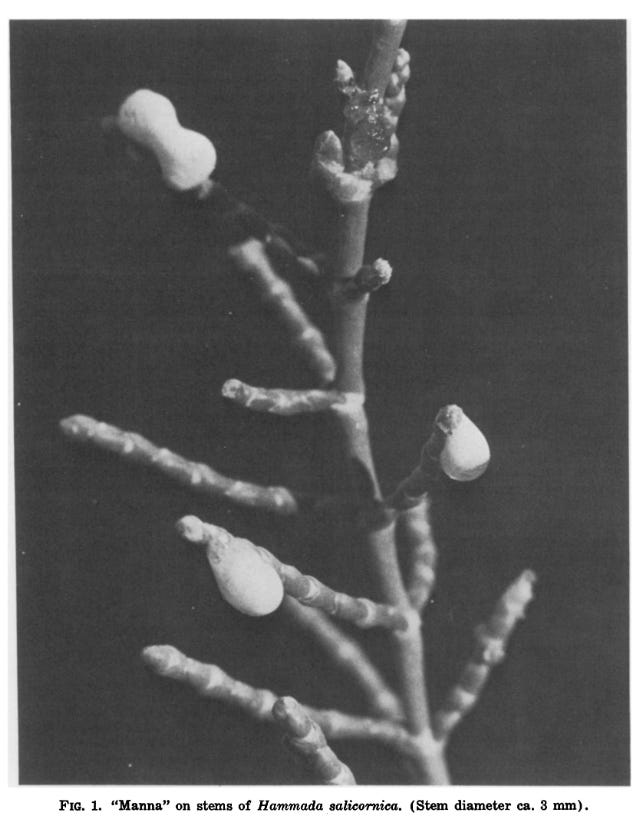

As they traveled deeper into the Sinai Peninsula, though, the desert offered up a pleasant surprise or two. First, there was “bread…from the sky” (Exodus 16:4 (J)): manna.

Now the manna was like coriander seed, and in color it was like bdellium.

The people would go about and gather it, grind it between millstones or pound it in a mortar, boil it in a pot, and make it into cakes. It tasted like rich cream.

When the dew fell on the camp at night, the manna would fall upon it. (Numbers 11:7-9 (J))

Mysterious food particles that show up near the ground in the Sinai actually do exist. The funny thing is that they’re bug poop. Wikipedia:

Honeydew is a sugar-rich sticky liquid, secreted by aphids, some scale insects, and many other true bugs and some other insects as they feed on plant sap. When their mouthpart penetrates the phloem, the sugary, high-pressure liquid is forced out of the anus of the insects, allowing them to rapidly process the large volume of sap required to extract essential nutrients present at low concentrations.

An Israeli botanist published this photo in 1972:

His observations seem even-handed:81

An area [in the Sinai Peninsula]…is quite densely covered by [the desert shrub Hammada salicornica, since renamed Haloxylon salicornicum]…In July 1968 I found sweet white drops on Hammada stems at Wadi Feiran [in the Sinai], while in May, 1969, which was a rainy year, hundreds of the shrubs in the sandy plain at Dabet el Qerai…were covered with similar drops 4 to 10 mm long…It is not yet clear what caused the secretion, but near every drop was the skin of an insect 1 mm long. Although the species of insect has not yet been determined, it is clear that they are infecting young vigorously growing shoots.…

Many authors have reported sweet secretions on plants in Sinai and I have found them on the following species, besides the Hammada: Anabasis setifera, Tamarix nilotica…, Acacia raddiana, Capparis cartilaginea, C. spinosa var. aravensis, Astragalus echinus, Pyrethrum santolinoides and Gomphocarpus sinaicus. All of them are regarded by the Bedouin as kinds of manna.

Bodenheimer (1947)…thought that the main source of manna was the honey-dew excretion of scale insects (Trabutina mannipara and Najacoccus serpentina [now Trabutina serpentina]) on tamarisk shoots. This excretion crystallises in dry air as a pure white substance. … Unfortunately, tamarisk trees…are infrequent in Sinai. There are, however, several concentrations in large wadis…It seems reasonable, therefore, to assume that not one [plant] species was the source of manna but any or all of those listed above, with Hammada salicornica as the main source in view of its relative abundance.

The quail that the Children of Israel fed upon (Numbers 11:31-35 (J)) were likely also real. Quail migrate from Africa to Europe, and a 2017 study82 notes that quail bones were found in multiple very old cultic and burial sites in the Sinai:

The quail (Coturnix coturnix) is a migrant species, found in Sinai and in [the] Eilat region primarily in the spring and autumn…Traditionally the Bedouin exploited this annual migration by catching the birds in vertically erected nets. The presence of quail bones in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B habitations of Wadi Tbeik in Sinai indicates that the migration of this species has been an annual event in the desert region for many millennia.

So, though the Pentateuch in its canonical form surely does exaggerate the quantities (e.g. “The Israelites ate the manna for 40 years” (Exodus 16:35 (P)), it’s plausible that fortuitously-appearing honeydew and quail did supply the desperate wanderers with some badly needed calories, which surely would have bolstered Moses’ claims of a personal connection with the god of the ʿIvrim.83

“To Your Tents, O Israel!”

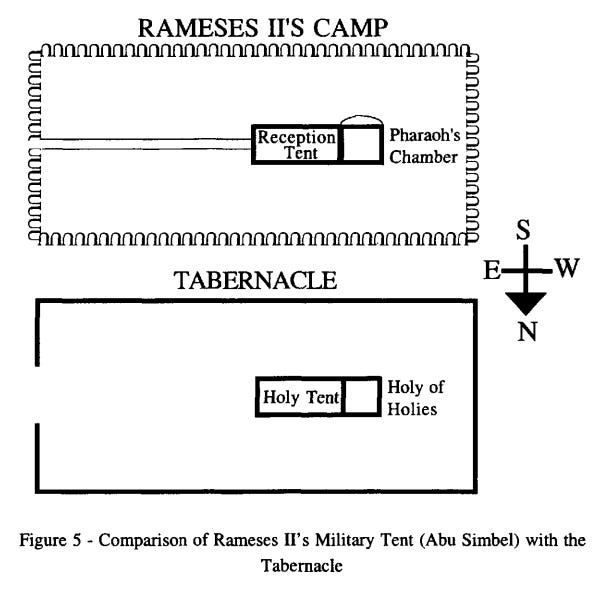

The Yahwa were nomads accustomed to harsh environments, but the Children of Israel weren’t: they had mostly lived in a relatively benign part of the eastern Nile Delta. Nor were they accustomed to traveling together in a big group. To survive, they needed organization and discipline. And they got it, I think, from Hur, Moses’ Egyptian bodyguard. That’s why, as Michael Homan pointed out, the description of the Sinai wanderers’ camp in the P source closely resembles “the military camp of Rameses II at Qedesh” (where his army battled the Hittites):84

The four reliefs and corresponding written sources of the battle of Qedesh portray a 2:1 rectangular camp, the entrance of which is in the middle of the short wall. Directly in the camp’s middle lies the entrance to a 3:1 long-room tent, composed of a 2:1 reception tent leading to the square throne tent of the pharaoh. Furthermore, we learn from the Abu Simbel relief that the height of Rameses's tent corresponds to its width. All of this matches the description of the Tabernacle and its camp in Exodus 25-27. Moreover, Rameses’s tent is oriented eastward.…The campaigning Egyptian army is divided into four units, as Israel encamps and marches by four standards according to Numbers 2. In sum, the military tent and camp of Rameses II at Qedesh constitute the best parallel to the Tabernacle known to date.

…The rectangular shape shared by Rameses’s camp and the Tabernacle is extraordinary; most military camps are elliptical.

At the center of the pharaoh’s camp was the pharaoh; at the center of the Exodus camp were Moses, his family, and his two lieutenants, Aaron and Hur, all surrounded by the Children of Israel.

It’s even possible that the supernatural-sounding pillar(s) of cloud and fire that guided the Children of Israel through the desert had some basis in fact. William Propp argued that this concept “recalls a military practice attested from ancient Greece and modern Arabia, but not yet from the ancient Near East. Quintus Curtius records that a beacon was borne atop a pole before Alexander’s army, ignis noctu fumus interdiu ‘fire by night, smoke by day.’ Until recently, Arab caravans, including the ḥajj, were preceded by a signal brazier. If ancient Israel knew such a custom, it might partly explain the symbol of the fiery-cloudy pillar.”85

What Happens on Sinai Stays on Sinai

According to the P source, three months passed between the “departure from Egypt” and the arrival in “the wilderness of Sinai” (Exodus 19:1). Then, on Mt. Sinai — or Mt. Horeb, as the E source (and, following it, the D source) calls it — something happened, maybe. But what?

The oldest version of the story that has survived, from the J source, is quite bare-bones.86 The hopeless, exhausted Children of Israel are increasingly skeptical of Moses’ divine sponsorship, asking, “Is YHWH present among us or not?” So YHWH decides to silence the haters by making a personal appearance:

YHWH said to Moses, “Go to the people and warn them to stay pure today and tomorrow. Let them wash their clothes. Let them be ready for the third day; for on the third day YHWH will come down, in the sight of all the people, on Mount Sinai.

But the rank and file aren’t allowed to get a close look. (“Whoever touches the mountain shall be put to death.”) Only “Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu [Aaron’s sons], and the seventy elders of Israel” go up Mt. Sinai.

…and they saw the God of Israel: under his feet there was the likeness of a pavement of lapis lazuli,87 like the very sky for purity. Yet he did not raise his hand against the leaders of the Israelites — they beheld God.

No thunder and lightning, no smoke, no horn-blast, no stone tablets — all of that comes from the later E source.

Reading between the lines, I think that what we have here is a bit of a conspiracy. The escape from Egypt had gone so badly that the Children of Israel couldn’t help but begin to distrust Moses and regard his authority as illegitimate. But, for better or for worse, Moses was the only leader they had; there were too many elders for any one of them to command the loyalties of the whole group. Disunited, they would never make it out of the desert alive. So Moses prevailed upon the elders to go along with the Yahwa story. They all went up a mountain out of view together and then came back saying, “Wow, yeah, we totally saw Yahwa. He was standing on a blue thing. It was amazing. Moses is telling the truth, and we should all keep following him.” Maybe it looked contrived, but the Children of Israel preferred not to start fights with their elders, so they went along with it. And now it was harder for the elders to turn on Moses, or at least on Yahwa: they had staked their own reputations on the new cult.

Onward to Canaan, or Not

According to the P source, Team Moses and the Children of Israel spent around a year in the “wilderness of Sinai” (Numbers 10:11-12).88 Then, relying on the navigational guidance of Moses’ nomad brother-in-law Hobab (Numbers 10:29-33 (J)89), the group headed from Sinai toward Cis-Jordanian Canaan. That was the original destination, after all: “a good and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey.”

According to the official story — which I find quite strange — Moses paused just south of Canaan and sent a handful of spies to scope out the Negev and beyond. They got at least as far as the city of Hebron. But they were scared of what they saw:

This is what they told [Moses]: “We came to the land you sent us to; it does indeed flow with milk and honey…However, the people who inhabit the country are powerful, and the cities are fortified and very large…” (Numbers 13:27-28)

Only Caleb, son of Jephunneh, had a positive attitude. So Moses threw up his hands and gave in to the wimps. Instead of heading straight into Canaan, they would retreat back into the wilderness.

All of that almost makes sense, but then, instead of feeling relieved that they wouldn’t have to confront powerful people and fortified cities, “the people were overcome by grief. Early next morning they set out toward the crest of the hill country, saying, ‘We are prepared to go up to the place that YHWH has spoken of, for we were wrong’” (Numbers 14:39-40 (J)). Wait, why are they suddenly so gung ho? And why does Moses now oppose their plan (Numbers 14:41-43 (J))?

But Moses said, “This will not succeed. Do not go up, lest you be routed by your enemies, for YHWH is not in your midst. For the Amalekites and the Canaanites will be there to face you, and you will fall by the sword…

Huh? Moses was just telling them to go to Canaan five seconds before! He was mad that they didn’t want to! Why the change of heart?

My guess is that it was Moses, not the spies, who got cold feet at the last minute. He (correctly) predicted that his little group was too vulnerable to stand up to possible Canaanite opposition. But some of the Children of Israel, sick of all the wilderness wandering, broke away and tried their luck with the direct approach. Before long, they were captured or killed.

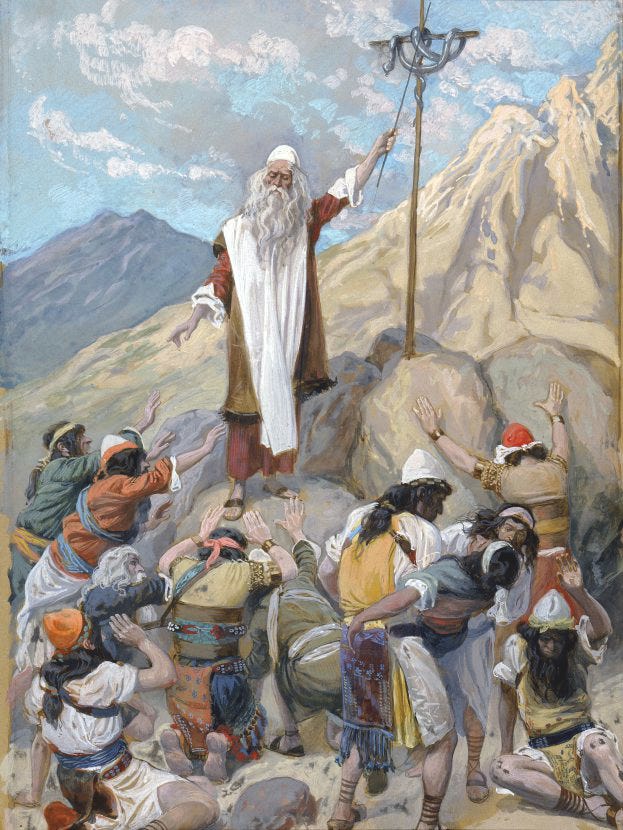

At Last…Nehushtan!

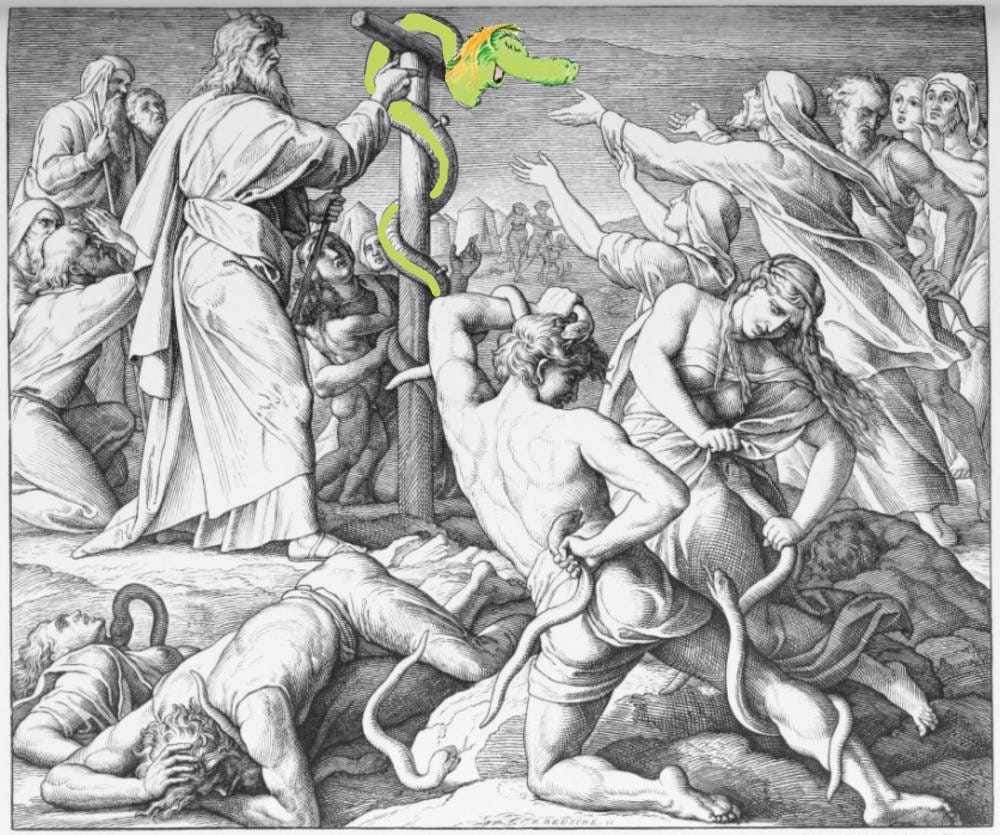

For the rest of the group, the slog continued. They went southeast toward the Gulf of Aqaba, passing through the copper-rich region of the Timna Valley that formed part of the Yahwa/Kenite territory discussed above. I suspect that around here90 is where Moses obtained a very special artifact: the bronze snake known as Nehushtan.

Recall that, at both the western and eastern ends of the Egyptian route to Midian and Arabia, there were statues of the goddess Hathor, who was supposed to protect travelers against snakebites. The 5-inch-long bronze snake found at the Timna shrine has been interpreted as a votive offering — that is, a gift to the goddess, intended to gain her favor. There was a long-lived Egyptian tradition of such votive offerings, especially to Hathor, and they could take the form of a range of smallish objects, including ceramic baboons and little naked-lady figurines, often made in official temple workshops91 and presumably purchased by worshippers. There was also a tradition of purposely breaking these offerings.92

I speculate that Moses encountered a Hathor shrine around Timna, got his hands on a copper-snake votive object, and intended to use it to cure snakebites if necessary, perhaps by ritually destroying it.93 Sure, he was Yahwa’s servant, but he was still an Egyptian!

Here’s how the official story goes in the Pentateuch:

…the people grew restive on the journey, and the people spoke against God and against Moses, “Why did you make us leave Egypt to die in the wilderness? There is no bread and no water, and we have come to loathe this miserable food.”

YHWH sent seraph serpents against the people. They bit the people and many of the Israelites died.

The people came to Moses and said, “We sinned by speaking against YHWH and against you. Intercede with YHWH to take away the serpents from us!” And Moses interceded for the people.

Then YHWH said to Moses, “Make a seraph figure and mount it on a standard. And if anyone who is bitten looks at it, he shall recover.”

Moses made a copper94 serpent and mounted it on a standard; and when anyone was bitten by a serpent, he would look at the copper serpent and recover. (Numbers 21:4-9 (E))

(What the heck are “seraph serpents”? It’s not totally clear, but probably cobras or cobra-like snakes of various sorts.95)

I think we can be fairly confident that Moses’ bronze snake was a real thing, because, some 500 years later, it was destroyed at the behest of King Hezekiah of Judah, as part of his campaign against unorthodox worship (2 Kings 18:4):

He abolished the shrines and smashed the pillars and cut down the sacred post. He also broke into pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until that time the Israelites had been offering sacrifices to it; it was called Nehushtan.

(Nᵉḥushtan is probably wordplay of some sort — naḥash is Hebrew for snake; nᵉḥoshet is Hebrew for copper/bronze.)

Strikingly, Nehushtan is never mentioned in the J or P sources. The southern Yahwist tradition that they represent tried hard to de-Egyptianize the story of the Exodus. According to this tradition, Moses was just a regular Child of Israel, not connected to the pharaonic line at all; there was no Hur; there was no bronze snake associated with Hathor. But the northern tradition, represented by the E source, was far less shy about Egyptian associations, for reasons we will eventually get to, so, fortunately, the story of Nehushtan was preserved.

Anti-Climax

In the P source (expanding on an idea already present in the earlier J source (Numbers 14:20-24)), YHWH, incensed that the wimpy Children of Israel refuse to go directly into Cis-Jordanian Canaan, decrees a harsh punishment:

Your children who, you said, would be carried off—these will I allow to enter; they shall know the land that you have rejected.

But your carcasses shall drop in this wilderness, while your children roam the wilderness for forty years, suffering for your faithlessness, until the last of your carcasses is down in the wilderness.

You shall bear your punishment for forty years, corresponding to the number of days—forty days—that you scouted the land: a year for each day. Thus you shall know what it means to thwart Me.

I, YHWH, have spoken: Thus will I do to all that wicked band that has banded together against Me: in this very wilderness they shall die to the last man. (Numbers 14:31-35 (P))

The figure of 40 years was thus engineered to provide enough time for the first generation of Egypt escapees to fully die off. Again, there’s a bit of a conspiracy afoot. In the event that post-Exodus skeptics ask their leaders if any of them actually saw Yahwa themselves, there’s a readymade answer: no, because everyone who did died before getting to the Promised Land.

…None of the men who have seen My Presence and the signs that I have performed in Egypt and in the wilderness…shall see the land that I promised on oath to their fathers… (Numbers 14:22-23 (J))

How convenient!

It’s implausible that the group spent 40 years wandering in the deserts of the Sinai Peninsula, but the text of the early sources doesn’t really require this; the large majority of that time was probably spent in the less forbidding regions to the south and east of the Dead Sea (Moab, Edom, and Seir).

This period was probably depressing. Presumably many of those who had left Egypt really did die. We’re told that Miriam died in Kadesh (Numbers 20:1 (E)), and Aaron died on Mt. Hor (Numbers 20:28-29 (P)). There was plenty of grumbling:

The people quarreled with Moses, saying, “If only we had perished when our brothers perished at the instance of YHWH! Why have you brought YHWH’s congregation into this wilderness for us and our beasts to die there? Why did you make us leave Egypt to bring us to this wretched place, a place with no grain or figs or vines or pomegranates? There is not even water to drink!” (Numbers 20:3-5)

And then, in the plains of Moab, northeast of the Dead Sea, Moses died too. Many excuses would be made for why Yahwa’s right-hand man never succeeded in his mission of uniting all the ʿIvrim in “a land flowing with milk and honey,” but, from an outside view, it sure looked like proof that Moses was not divinely inspired, just a strange, ambitious man whose reach exceeded his grasp.

The New Twelve Tribes of Israel

From an inside view, though, the sheer fact that (some of) the Children of Israel had managed to survive so many harrowing experiences — eluding the Egyptian army, living in the desert, getting within less than a day’s journey of Cis-Jordanian Canaan — seemed miraculous. They were not about to give up on Team Moses so easily. If nothing else, it would have been embarrassing. Having gone through so much together, the Children of Israel and the families of Moses, Aaron, and Hur were now a single people.

At some point, back in Egypt, the Children of Israel had come to see themselves as divided into twelve clans, each tracing its roots back to a venerated namesake ancestor: Asher, Naphtali, Zebulun, Issachar, Manasseh, Ephraim, Dan, Gad, Reuben, Benjamin, Simeon, and Judah. The families of Moses, Aaron, and Hur were now regarded as constituting a new Israelite clan, tacked on — attached — to the old ones. And that was the source of their clan name: the Levites, or “attached people.” Here I am drawing on a case made by William Propp:96

There is a large literature on the etymology of lēwî…Among the proposals are “Attached one,” i.e., to God…To my knowledge, no one has suggested that lewî indeed means “attached person” in the sense of “sojourner, resident alien.” Thus lēwî would be quasi-synonymous with gēr; cf. Isa 14:1: wənilwâ haggēr ʿălêhem wənispəḥû ʿal-bêt yaʿăqōb ‘the sojourner will be joined (lwy) to them and they will be attached to Jacob’s House.’

There was just one little problem. For whatever reason, the Children of Israel saw 12 as the right and proper number of ethnic subdivisions; the Ishmaelites, too, they said, had “twelve chieftains of as many tribes” (Genesis 25:16 (P)). So when they added the Levites as a new tribe, an old tribe would have to go. The solution was a simple, if inelegant, hack: recharacterizing Ephraim and Manasseh as “half-tribes” making up a single whole tribe of Joseph.

Over time, just as, say, the Judahites were seen as descendants of Judah, so too were the Levites seen as descendants of a son of Israel named Levi, who was created out of whole cloth. But the traditional three-part division of the Levites into Gershonites, Merarites, and Kohathites betrayed the true origins of this synthetic tribe. I propose that the Gershonites were the descendants of Moses, whose elder son was named Gershom; the Merarites were the descendants of Hur, perhaps named after his (postulated by me but not attested in the Bible) son Merari (notably, an Egyptian name meaning “beloved of Ra”97); and the Kohathites were the descendants of Aaron, though I don’t know where the name came from. (As we will see, Aaron’s lineage would rewrite a lot of history.)

A Stroke of Good Luck

If the 40-ish year duration of the Exodus is to be believed, then it was around 1190 BCE that some of the Israelites — a term I have tried to reserve for the fusion of the old Children of Israel with the families of Moses and his lieutenants — began to venture west of the Jordan River. The timing is quite interesting and, for the Israelites, lucky. Ramesses III — the pharaoh who fended off the Sea Peoples — sat on the Egyptian throne. It was during his reign that Egypt, faced with economic and military challenges at home, began to let its imperial possessions in the Levant gradually slip away. The resulting power vacuum made it easier for interlopers like the Israelites to horn in on territory that had once been part of the Egyptian sphere of influence.

But the luck wasn’t all good. Starting at perhaps the exact same time — 1173 BCE ±17 years98 — the same opportunity also began to be exploited by an offshoot of the Sea Peoples: the Philistines. The Philistines, I have argued, were mainly Greek-speaking (at first) and mainly hailed from Crete. They had taken up residence on the southwestern coast of Anatolia, but, as Egypt gave up on the Levant, the Philistines established a foothold on the coast of Canaan. The presence of the Philistines would insure that the initial Israelite expansion would be confined to the less desirable hill country.

But, like the compiler of the Pentateuch, I’ll stop here, right after the death of Moses.

To be continued. You won’t want to miss the next installment — I’ll tell you how tall God is!

Date from Kitchen et al. 2009, “Bayesian phylogenetic analysis of Semitic languages identifies an Early Bronze Age origin of Semitic in the Near East.” I don’t particularly want to litigate the niceties of linguistic vs. ethnic vs. genetic inheritance here, but see my “notes toward Proto-World” (part 1 and 2) for my general approach.

The phrasing and much of the substance come from Burke 2021, The Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East: The Making of a Regional Identity.

“Amurru” is technically an Akkadian borrowing from Sumerian, but I assume that the pronunciation of the Sumerian word (obscured by the writing system) was similar.

Burke 2021, p. 363.

See e.g. Flammini 2010, “Elite Emulation and Patronage Relationships in the Middle Bronze: The Egyptianized Dynasty of Byblos.”

See Rich et al. 2016: “Multiple texts cite Byblos as the port where cedar wood was acquired, but these do not date earlier than the New Kingdom...So although it has long been surmised that Egyptian cedar imports came from the Lebanon, these results are the first direct indication that Lebanese cedar was exported to Egypt as early as the Middle Kingdom.”

I’m stating this more straightforwardly than I’ve seen any academic do, but I feel pretty confident that this is what was going on at Serabit el-Khadim. On this topic, I got a lot out of Parker 2022, “The Proto-Sinaitic Inscriptions at Serabit el-Khadim in Their Archaeological Context,” though the author finds the hypothesis of a Byblos link “dodgy.” See also Pomey 2018, “The Rock Engravings of Boats of Sinai and the Pharaonic Maritime Expeditions.”

Linking the alphabet to the Byblian state helps explain the otherwise strange fact, emphasized by Richey 2023, that “a half-century of excavation at Avaris has turned up precisely zero alphabetic texts.” Avaris had Byblians, but it may not have had the Byblian royal scribes. The 1850 date is my own guess, based mainly on Parker 2022.

Vita and Zamora 2018: “Byblos’ relationship with writing was indeed prolonged and intense. The Egyptian Hieroglyphic script was well known there at least from the middle of the third millennium BC…and all clues indicate that in the ensuing millennium, scribes in the city, or scribes who frequented it, were able to use it.” Holmstedt 2019: “it is odd that the Byblians have not been suggested more often as the most likely source for the alphabet.”

Richey 2023 argues that people should care more about a bit of possible alphabetic writing, dating as far back as the Early Bronze Age, found at the site of Umm el-Marra (plus another bit in Mesopotamia from a later date). I don’t know how seriously to take this case, but the nice thing from my perspective is that Umm el-Marra was an Amorite site, so either way I can still say that the Amorites invented the alphabet.

Burke 2021, p. 146. See also Burke 2019, “Amorites in the Eastern Nile Delta: The Identity of Asiatics at Avaris during the Early Middle Kingdom.”

Mourad 2015, Rise of the Hyksos: Egypt and the Levant from the Middle Kingdom to the Early Second Intermediate Period, p. 202.

Derived from my own ChronoLog model, but the chronology of the Second Intermediate Period is a mess. See Höflmayer 2018, “An Early Date for Khyan and Its Implications for Eastern Mediterranean Chronologies”; Höflmayer and Manning 2022, “A Synchronized Early Middle Bronze Age Chronology for Egypt, the Levant, and Mesopotamia”; Mahieu 2021, “The Identities of the Second Intermediate Period Dynasties in Egypt”; Mahieu 2023, “The Identification and Sequence of the Hyksos Kings in Dynasty 15.”

Derived from my ChronoLog model.

Genesis 37:2 (J).

I felt clever for noticing the similarity of the Amorite style to Joseph’s coat, but then I saw that it was mentioned matter-of-factly in Wikipedia.

The 1500 date comes from Kitchen et al. 2009. See also Wilson-Wright 2019, “The Canaanite Languages,” in The Semitic Languages (2nd ed.), p. 509: “As a family, the Canaanite languages are attested from roughly 1360 BCE to 400 CE with Proto-Canaanite dating no earlier than 1550 BCE.” Incidentally, this makes it seem less anomalous that, in the Deuteronomic Code, Israelites are instructed to say, “My father was a fugitive Aramaean. He went down to Egypt with meager numbers and sojourned there; but there he became a great and very populous nation” (Deuteronomy 26:5, JPS 1985 translation, emphasis added). When Joseph and his relatives settled in Egypt, the distinction between Aramaean and Canaanite was still blurry.

In general I am following the “neodocumentary” J/E/P/D source attribution from Baden 2012, The Composition of the Pentateuch: Renewing the Documentary Hypothesis, cross-referenced with Feldman 2023, The Consuming Fire: The Complete Priestly Source.

I’ve dumped what I think are the texts of the J source, E source, and D source on Rentry.co, along with the P-source parts of Genesis and Exodus and Numbers and Deuteronomy. (All of Leviticus is P.) The format and structure are pretty janky, but hopefully it’s better than nothing.

Based on various clues, I think we can pin down Abram’s birth year to 1780 BCE ±9 years, though I admit that sounds crazily precise.

This is clearest in P (Genesis 11:31). What we have of J doesn’t explicitly identify Abram’s hometown, but in Genesis 24:4 Abram tells a servant to “go to the land of my birth and get a wife for my son Isaac.” The servant then goes “to Aram-naharaim [‘Aram between the rivers’], to the city of [Abram’s brother] Nahor” (Genesis 24:11), and encounters Nahor’s grandson Laban, later said in J to live in Haran (Genesis 27:43).

Richard Elliot Friedman’s translation from The Bible with Sources Revealed. Unless otherwise noted, though, I’ll be using the JPS 1985 translation from Sefaria but swapping out “the LORD” for “YHWH.”

See Stephanie Dalley, The City of Babylon: A History, c. 2000 BC–AD 116 (2021), “Appendix: Genesis 14:1–16 and Possible Links with Foreign Rulers Early in the Reign of Hammurabi” and p. 68: “The discovery that Elam was a superpower at this time, with influence spreading at least as far as Qaṭna on the river Orontes in Syria, and probably as far as Haṣor in Palestine, has made it fruitful to reinvestigate an old idea, that the story of Kedor-laomer king of Elam (whose name is Elamite) in Genesis 14:1–16 contains a core of historical information from this period.” Following Dalley, we have the following equivalencies:

Biblical “Chedorlaomer, king of Elam” = Elamite Kudur-Lagamar (not attested but linguistically plausible)

Biblical “Amraphael, king of Shinar” = garbled mix of Hammurabi of Babylon and Amud-pi-El of Qaṭna

Biblical “Arioch, king of Ellasar” = Arriuk, an Elamite vassal in Upper Mesopotamia

Biblical “Tidal, king of Goiim” = Tudhaliya, a Hittite leader (pre-dating the Hittite conquest of Hatti and the several kings also named Tudhaliya)

I disagree with Dalley, though, about the Horites of Genesis 14:6 — they’re not Hurrians but rather a Trans-Jordanian Canaanite people also mentioned elsewhere in the Bible.

See Burke 2021, “Toward the Reconstruction of a Sacred Landscape of the Judean Highlands.” Jerusalem was probably founded as an Amorite city, named after Šalem, an Amorite god.

Melchizedek’s role is a bit unclear, but I conjecture that he was basically mediating between Abram and the king of Sodom. (Jerusalem is roughly at the intersection of the path north from Hebron and the path west from Sodom, assuming that Sodom was or was close to Tell el-Hammam, which I believe, although admittedly a lot of the people who push this idea seem…unreliable.) Genesis 14 suggests that, at the time of the Jerusalem parley, Abram hadn’t yet handed back Sodom’s “persons” or “property.” The king was prepared to accept the return of only the captives, allowing Abram to keep the stuff, presumably with the implied threat that if Abram got greedy and additionally demanded ransom for the captives, the king would switch from negotiation to violence. Melchizedek served as a neutral third party to encourage peaceful deal-making, which helps to explain why he received “a tithe from everything,” i.e. a share of the property in question. As it so happened, Abram was such an honorable guy that he just gave back everything and everyone taken from Sodom, “except only what the boys have eaten” and the portion of the loot that his Amorite homies had expected to keep.

Richard Elliot Friedman’s translation from The Bible with Sources Revealed.

Why is Israel also called Jacob? I’m not sure, but I think “Israel” is the authentic name and “Jacob” a later invention. The Bible speaks of the “tribes of Israel” many times, but the phrase “tribes of Jacob” appears only once. “Israel” as a name for this group is also attested in an ancient Egyptian text, as we will see. And the altar that “Jacob” creates in Shechem (Genesis 33:20 (E)) is called “El-elohe-yisrael” — El, god of Israel — even though at that point in the E story the name “Israel” hasn’t appeared yet. (It starts popping up later in E in the Joseph story, but there’s no explicit E narrative of Jacob changing his name.)

My guess: in the northern Yahwist tradition represented by the E source, it wasn’t a big deal for “El” to be part of Israel’s name, because in his time YHWH hadn’t yet revealed his own name to humans. In the southern/J tradition, however, YHWH’s name was known since at least the time of Enosh (Genesis 4:26 (J)), before the Flood, so it was awkward that Isaac and Rebekah, who had had direct personal encounters with YHWH, would name their son something-El. But the name “Israel” was too well known and too embedded in e.g. the Joseph story to just eliminate, so J created a kludge-y fix: Israel was born “Jacob,” but his name changed later. The story of the name change was shoehorned into a pre-existing tradition about a non-divine wrestling incident in the vicinity of the Jabbok River. But it turned out that the E source contained a version of this same tradition. When the J and E accounts were merged into the Pentateuch, the resulting mishmash of (wrestling + divine name-change) + (wrestling + thigh injury) led to the notoriously baffling composite scene of Jacob wrestling with the angel.

“A caravan of Ishmaelites coming from Gilead,” with “camels” (Genesis 37:25 (J)). Is it historically accurate (and not merely conventional) to equate Ishmaelites with Arabs, and does the geography make sense? I think so. Cf. 1 Chronicles 5:10, saying that “in the days of Saul” the tribe of Reuben “made war on the Hagrites…east of Gilead” (Ishmael was the son of Hagar), and 1 Chronicles 5:19-20, referring to Reuben, Gad, and Manasseh fighting the Hagrite subgroups “Jetur, Naphish, and Nodab” (Jetur and Naphish are listed as sons of Ishmael in Genesis 25:15 (P)). So there were Hagrites/Ishmaelites east of Gilead. And this was the same area where Old Arabic inscriptions using the Ancient North Arabian Safaitic script later cropped up. See Al-Jallad, “Safaitic,” in The Semitic Languages, 2nd ed. (2019), p. 342-4.

The tricky part, actually, is the camel reference. One might think that Arab-owned camels would be one-humped dromedaries, domesticated in southeastern Arabia, but there’s a problem: these may not have been domesticated early enough for the Joseph story and maybe not even the writing of the J source. But two-humped Bactrian camels were domesticated earlier, and Genesis links them to modern-day Syria, northeast of Gilead, so it’s not too implausible that Syrian Arabs c. 1610 BCE would have had access to camels. See Heide and Peters, Camels in the the Biblical World (2021), p. 240.

Translating the Biblical Hebrew words for these items is difficult. The best guesses from Heide and Peters, Camels in the the Biblical World (2021), 4.2.4.1, are:

gum of tragacanth, derived from “the evergreen shrub Astragalus gummifer and Astragalus tragacantha, used in food and medicine”

a balm (the famous balm of Gilead) derived from the oriental sweetgum tree

“the gum obtained from the pink or hoary rock rose, Cistus incanus (L.), widely distributed across the eastern Mediterranean”