“Get Yourself Another Scroll” (Jer 36:28)

The real (?!) story of Moses and the Israelites, part 2.

[Part 1.]

North and South

When last we left the Israelites, it was around 1190 BCE, and they were encamped a bit to the northeast of the Dead Sea, but some were beginning to venture west, across the Jordan River and into the heart of Canaan.

As the Israelites settled throughout Canaan — taking advantage of looser and then nonexistent Egyptian imperial control, as discussed in Part 1 — they mixed with the narrow- and broad-sense Canaanite peoples already living there and began to speak a form of their language. This new Israelite dialect of Canaanite is what we now call “Hebrew.” (A similar process of language assimilation also unfolded among the Philistines, who went from mostly speaking a Mycenaean-like form of Greek to speaking their own Canaanite dialect.1)

The Israelite expansion probably wasn’t well-organized. Moses and Aaron (and, I would guess, Hur) had died, leaving the group without a clear leader. Two men filled the vacuum: Caleb and Joshua. (The E source doesn’t mention Caleb; the J source doesn’t mention Joshua.)

We don’t know much about Caleb, other than that, supposedly, he was the only one of the scouts dispatched by Moses who was enthusiastic about the prospect of occupying Canaan. According to the story, YHWH rewarded him for his faith with a promise of land:

My servant Caleb, because he was imbued with a different spirit and remained loyal to Me—him will I bring into the land that he entered, and his offspring shall hold it as a possession. (Numbers 14:24 (J))

Caleb and his allies — mainly fellow members of the tribe of Judah, as well as Yahwa/Kenite people related to Moses’ father-in-law2 — crossed the Jordan and went south into what came to be known as the Judean hill country. They did at least a bit of conquering:

The Judahites marched against the Canaanites who dwelt in Hebron, and they defeated Sheshai, Ahiman, and Talmai. (The name of Hebron was formerly Kiriath-arba.) … They gave Hebron to Caleb, as Moses had promised… (Judges 1:10, 1:20)3

Elsewhere, too, the J source takes a conspicuous interest in Hebron (most glaringly in the seemingly unnecessary parenthetical “Now Hebron was founded seven years before Zoan of Egypt” (Numbers 13:22)), and I think the reason is simple: the J source was composed in Hebron at the behest of Caleb’s descendants, probably around 1040 BCE.4

Included in Caleb’s southward-traveling band, I think, was the family of Aaron. Aaron was a Yahwa tribesman, so it made sense that his kin went with the other Yahwa. But, while the others ended up going farther south into the Negev, Aaron’s descendants stayed among the Judahites, and at least some of them acted as priests. From a southern Israelite perspective, these were the Levites: Aaron’s people.

Recall that the descendants of “Cain” were said to include not just the first metalworker but also “the ancestor of all who play the lyre and the pipe” (Genesis 4:21 (J)) — an etiology for the Yahwa/Kenites’ musicianship. Miriam, Aaron’s sister, shows up in the Exodus story chanting and shaking a tambourine (Exodus 15:20-21 (E)). This musical tradition was carried on by the southern “Levites” — Yahwa/Kenites who merged into the Children of Israel — well into the later monarchic period:

David spoke to the chief of the Levites to appoint their brethren the singers, with instruments of music, psalteries and harps and cymbals, sounding aloud and lifting up the voice with joy.5

But this southern/Judah/Caleb/Aaron contingent was only a minority of the Israelite population. Back up north, it was Joshua, the former “attendant” of Moses, who was first among equals, remembered as a great military leader who helped displace Canaan’s previous residents.6 Meanwhile, the “Levite” families of Moses and Hur, not Aaron, took on cultic roles.7 This early split between northern and southern Israelites prefigured the later divided monarchy.

“He Forsook the Tabernacle of Shiloh”

The Israelites set up Yahwist shrines and sanctuaries wherever they went. In Part 1, I characterized the pro-Yahwa agreement between Moses and the elders of Israel as a “conspiracy,” but a more neutral term would be “deal,” “pact,” or “covenant.” In the earliest version of the official story, it was, of course, Yahwa who had made the covenant with the Israelites. But it had nothing to do with moral uprightness broadly construed; it was entirely about loyalty to Yahwa. In large part, it was a covenant about covenants!

So he said: “I hereby make a covenant. Before all your people I will work such wonders as have not been wrought on all the earth or in any nation; and all the people among whom you live shall see how awesome are YHWH’s deeds which I will perform for you. Mark well what I command you this day. I will drive out before you the Amorites, the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites.

Beware of making a covenant with the inhabitants of the land against which you are advancing, lest they be a snare in your midst. No, you must tear down their altars, smash their pillars, and cut down their sacred posts; for you must not worship any other god, because YHWH’s very name is jealous — he is a jealous god.

You must not make a covenant with the inhabitants of the land, for they will lust after their gods and sacrifice to their gods and invite you, and you will eat of their sacrifices. And when you take wives from among their daughters for your sons, their daughters will lust after their gods and will cause your sons to lust after their gods.”

Then YHWH said to Moses: “Write down these words, for in accordance with these words I make a covenant with you and with Israel.” And he wrote down the words of the covenant.8

At this stage, there were no fixed rules about which Yahwistic altars were legitimate, but the most prominent ones in the north were at Bethel and Shiloh. The Bible is quite cagey about the fate of Moses’ family, but I speculate that both Bethel and Shiloh were initially presided over by descendants of Moses: the Gershonites.9 Notably, two of the priests associated with Shiloh in the Bible — Hophni and Phinehas, the wicked sons of Eli — had Egyptian names.10

Something bad happened to Shiloh. Around 1060 BCE — about 130 years after the Israelites began to move into the Cis-Jordan — “this settlement came to an end in an exceptionally heavy conflagration, which left destruction debris of over 1 m thick.”11 The culprit is unclear — Philistines? Ammonites?12 — but the casualties included Eli, Hophni, and Phinehas (1 Samuel 4). The line of Moses wasn’t quite snuffed out — Phinehas had at least two sons, Ichabod and Ahitub, who survived — but its prestige was badly damaged. Psalm 78, which might have been composed as early as the reign of King Solomon,13 casts the destruction as a rebuke:

...they defiantly tested God Most High, and did not observe His decrees. ... God heard it and was enraged; He utterly rejected Israel. He forsook the tabernacle of Shiloh, the tent He had set among men. ... He gave His people over to the sword; He was enraged at His very own. Fire consumed their young men, and their maidens remained unwed. Their priests fell by the sword, and their widows could not weep.

Against this backdrop, there arose within the northern Yahwist tradition an emphasis on inspiration over bloodline. What mattered wasn’t whether Moses was your grandfather or great-grandfather; what mattered was whether Yahwa spoke to you in dreams and visions.

The Footstool of God

In the south, Yahwism evolved differently. Reverence for Aaron’s lineage continued. One of the main Aaronid cultic sites was Kiriath-jearim, where, I believe, the concept of the “Ark” of Yahwa was born.14

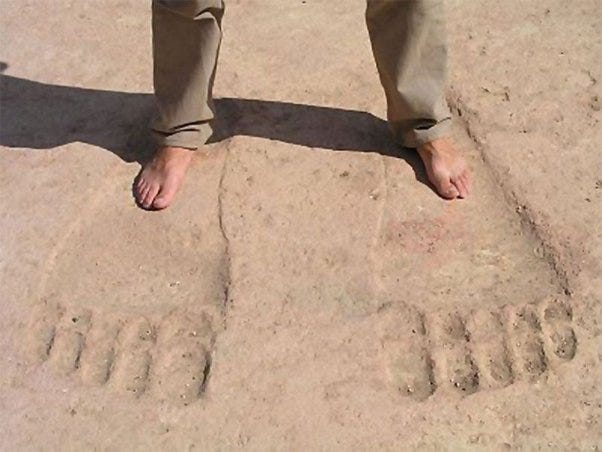

An ark — ʾărôn — was just a wooden box. Originally, though, I (and some, but certainly not all, scholars) think, it was a footstool — a place for Yahwa to rest his feet, perhaps so he could avoid directly touching a profane surface. (The E source, arising from a northern Israelite milieu, didn’t mention an ark at all, and I don’t think the original J source did either.15) Yahwa was bigger than any human, so he needed a big footstool — about the size of a desk, apparently. There are echoes of this notion in the Iron Age Syrian temple of Ain Dara, which sports a pair of carved stone indentations about one meter long each, representing divine footprints:

When David, a southerner, became king of (nominally) all Israelites around 1003 BCE16 and then conquered Jerusalem and made it his capital, it was the Aaronid talisman of the divine footstool that he seized upon to symbolize his Yahwistic bona fides, relocating it (by force17) from Kiriath-jearim to Jerusalem. (I think David also relocated the scroll of the J source from his previous capital of Hebron to Jerusalem. Since David had, during his rise to power, killed the Calebite chieftain and stolen his wife,18 the Caleb veneration in the J source ended up being a dead end.)

But David, seeking to unify the north and south, didn’t abandon the northern Mosaic lineage. Zadok, who claimed descent from Aaron, was only one of David’s official high priests; the other one was Abiathar, the great-great-grandson of the Shiloh casualty Eli. This north/south fusion required a bit of narrative finessing. A new, fanciful official story was invented: the Ark/divine footstool dated all the way back to the time of Moses and the Exodus and had initially resided in Shiloh, but it had been stolen by the Philistines. After Yahwa afflicted them with various plagues (including an outbreak of hemorrhoids (1 Samuel 5:9)), the Philistines meekly sent the Ark back to the Israelites on a driver-less, cow-drawn cart (1 Samuel 6), which just so happened to bring it to the southern land of Judah, where it wound up in Kiriath-jearim before David had it brought to Jerusalem. The point of this tall tale was to transfer Israelite reverence for Shiloh to the new cultic center in Jerusalem without treating northern traditions as illegitimate.

“A Faithful Priest”

But David’s ecumenical co-priesthood approach didn’t last long. His son Adonijah expected to succeed him to throne, and Abiathar, the priest from the Mosaic lineage, supported Adonijah. But Zadok, the Aaronid, supported a different claimant: Solomon.19 When Solomon defeated Adonijah, his first act of business was purging his enemies, including Abiathar:

To the priest Abiathar, the king said, “Go to your estate at Anathoth! You deserve to die, but I shall not put you to death at this time, because you carried the Ark of my Lord YHWH before my father David and because you shared all the hardships that my father endured.”

So Solomon dismissed Abiathar from his office of priest of YHWH… (1 Kings 2:26-27)

The invented story of the Ark’s time at Shiloh was revised to fit the new dispensation. Now the official line was that old Eli’s sons had been sinful “scoundrels,” and Eli was complicit in their crimes, so “YHWH was resolved that they should die” (1 Samuel 2:25) and that their descendants should lose their high status:

A man of God came to Eli and said to him, “Thus said YHWH: Lo, I revealed Myself to your father’s house in Egypt when they were subject to the House of Pharaoh, and I chose them from among all the tribes of Israel to be My priests—to ascend My altar, to burn incense, [and] to carry an ephod before Me—and I assigned to your father’s house all offerings by fire of the Israelites.

Why, then, do you maliciously trample upon the sacrifices and offerings that I have commanded? You have honored your sons more than Me, feeding on the first portions of every offering of My people Israel.

Assuredly—declares YHWH, the God of Israel—I intended for you and your father’s house to remain in My service forever. But now—declares YHWH—far be it from Me! For I honor those who honor Me, but those who spurn Me shall be dishonored.

A time is coming when I will break your power and that of your father’s house, and there shall be no elder in your house.

You will gaze grudgingly at all the bounty that will be bestowed on Israel, but there shall never be an elder in your house.

I shall not cut off all your offspring from My altar; [but,] to make your eyes pine and your spirit languish, all the increase in your house shall die as [ordinary] men.

And this shall be a sign for you: The fate of your two sons Hophni and Phinehas—they shall both die on the same day.

And I will raise up for Myself a faithful priest, who will act in accordance with My wishes and My purposes. I will build for him an enduring house, and he shall walk before My anointed evermore.

And all the survivors of your house shall come and bow low to him for the sake of a money fee and a loaf of bread, and shall say, ‘Please, assign me to one of the priestly duties, that I may have a morsel of bread to eat.’”

Thus Solomon’s dismissal of Abiathar was presented as “fulfilling what YHWH had spoken at Shiloh regarding the house of Eli” (1 Kings 2:27). Though the text (at least in its surviving form) doesn’t explicitly say which “father’s house” was being cast down and which “faithful priests”’s house was being raised up, I think it’s really about Moses’ descendants being subordinated to Aaron’s. The petty final line about how the survivors of Moses’ house would beg to be assigned some priestly duty in order to obtain even “a morsel of bread” was borne out in the later P (for “priestly”) source, which says that, among the Levites, it was the Gershonites who would carry the least holy items for Yahwa’s Dwelling Place, receive the fewest oxen and carts to help them,20 and stand in the least prominent position near the divine Meeting Tent (behind it21). To rub salt in the wound, in P, it is only the Gershonites, among the Levite subgroups, about whom it is explicitly said, “All [their]…labor and carrying duties should be done at the instruction of Aaron and his sons” (Numbers 4:27 (P)). The house of Moses would never live down the firing of Abiathar.

Over time, the sons of Zadok weren’t satisfied just having an exclusive claim to the high priesthood; they also wanted to rewrite history. Aaron would no longer be just Moses’ Yahwa/Kenite translator; he was now to be remembered as Moses’ brother — older brother, no less! Moses’ son Eliezer became Aaron’s son Eleazar (a difference of just one letter in consonantal Hebrew: ʾ-L-Y-ʿ-Z-R vs. ʾ-L-ʿ-Z-R), while Aaron’s real sons, Nadab and Abihu (depicted as perfectly legitimate heirs in the older J source), were retconned as having been divinely incinerated in the desert for some petty offense. Moses was far too central to Israelite culture to delete entirely, but he could be cordoned off. In the words of the scholar Liane Feldman,

in the priestly narrative Moses is presented as a singular figure—an anomaly in the larger systems created in the narrative. He is not a priest, but at times he offers sacrifices. He is not ordained or consecrated, yet he is allowed to repeatedly enter spaces that only consecrated individuals are allowed to enter. He alone is allowed to see Yahweh. Perhaps because of his unique status in the story, Moses also never marries, and he has no children.22

Yahwa may have stopped short of fully exterminating the house of Moses, but, within the influential fictions of the P source, priestly authors could go all the way.

The Temple, the Molten Sea, and the Oxen

Soon (around 967 BCE) King Solomon began to create something the Israelites had never had: an official temple building. The Bible contains a detailed, though at times confusing, description of this temple, which resembles several other ancient Near Eastern temples later uncovered by archaeologists. As far as I know, the most academically respectable reconstruction of what the Temple of Solomon looked like comes from Yosef Garfinkel and Madeleine Mumcuoglu, who collaborated with the architect Roy Albag:23

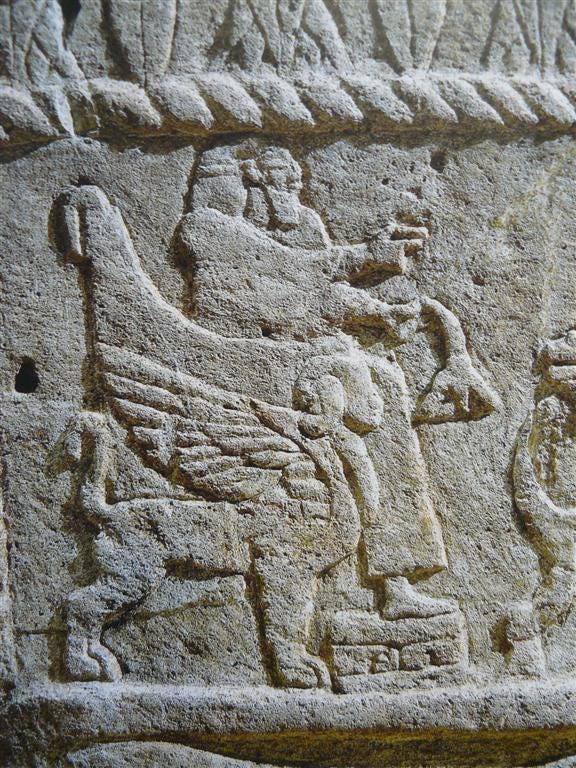

Inside the inner sanctum or “Holy of Holies” — which was a ~30x30x30-ft cube —Solomon’s priests positioned the Ark, flanked by two huge statues: “cherubim of olive wood, each 10 cubits [≈ 15 ft] high…overlaid…with gold” (1 Kings 6:23 and 6:28). What exactly these “cherubim” were is unclear. Liane Feldman asserts that they were “fearsome-looking animal statues, typically containing the parts of more than one type of animal,” not “chubby infants with wings”24; Raanan Eichler, though, argues that they actually were “winged humans” after all.25

Below is my own crude cartoon of the layout of the Holy of Holies, with Yahwa imagined as a big invisible guy sitting on an invisible throne, his feet protected by the holy Ark from touching the insufficiently holy floor. (The sphinxes pictured are from the 18th century CE, so don’t take them too literally.)

This setup resembles an image carved on the sarcophagus of Ahiram, a Phoenician king from roughly the same period:26

Based on my diagram, I estimate that Yahwa was around 16 feet tall. Good to know! There’s something quite appealing about a god who’s just a Really Big Guy — but not, like, cosmically big.

Even aside from the giant cherubim, the Temple was extravagant, perhaps even tacky. There were carvings of gourds and palm trees all over, and every surface of the inner sanctuary was “overlaid with gold” (1 Kings 6).27

The area just outside the Temple was also extravagant. In front of the entrance was the “Molten Sea” (yam mutsaq)28 (1 Kings 7:23), a huge bronze basin — 8 ft tall and 16 ft across — with no clear purpose other than decoration.

[The Molten Sea] stood upon twelve oxen, three looking toward the north, and three looking toward the west, and three looking toward the south, and three looking toward the east; and the sea was set upon them above, and all their hinder parts were inward. (1 Kings 7:25)

These oxen were probably also made of bronze and presumably symbolized the 12 tribes of Israel. Below is a reasonable reconstruction, though, in the absence of any concrete information in the biblical account, the size and stance of the oxen are just guesses:

In front of the bronze oxen and the Molten Sea was a bronze altar, on which Solomon presented and burned abundant sacrificial offerings of animals, grain, and fat (1 Kings 8:64). On the day of the Temple’s dedication alone, he “offered 22,000 oxen and 120,000 sheep as sacrifices of well-being” (1 Kings 8:63). In such sacrifices, only the suet was burned, and most of the meat could be eaten — “so Solomon and all Israel with him…observed the Feast at that time before YHWH our God, seven days and again seven days, fourteen days in all” (1 Kings 8:65).

None of this came cheap. In addition to extracting taxes and tribute, Solomon “imposed forced labor on all Israel” to carry out his many construction projects (1 Kings 5:27). These displays of wealth and power redounded to the glory of not just the king but also his Aaronid high priest, Zadok. Not everyone, though, was on board.

The Tale of the Molten Calf

Solomon’s depredations were very unpopular. Beyond the practical reasons, some Yahwists, especially in the north, felt that the gaudy new temple violated the true spirit of their cult. Worship of Yahwa was supposed to be simple and austere — according, at least, to the E source, the earliest form of which was, I think, composed around this time:

YHWH said to Moses:

Thus shall you say to the Israelites: You yourselves saw that I spoke to you from the very heavens:With Me, therefore, you shall not make any gods of silver, nor shall you make for yourselves any gods of gold.

Make for Me an altar of earth and sacrifice on it your burnt offerings and your sacrifices of well-being, your sheep and your oxen; in every place where I cause My name to be mentioned I will come to you and bless you.

And if you make for Me an altar of stones, do not build it of hewn stones; for by wielding your tool upon them you have profaned them. (Exodus 20:19-23 (E))

The E-source authors rejected the idea of a centralized, privileged cultic site like the Temple: “in every place where I cause My name to be mentioned I will come to you and bless you,” not just in some fancy new building in Jerusalem. And they also cast doubt on a centralized, privileged priesthood. What was so great about descending from Aaron anyway? He was just a follower of Moses, no better than Hur — quite possibly worse. The E-source authors created a story to dramatize their contempt for the sons of Aaron and their unholy bling:

When the people saw that Moses was so long in coming down from the mountain, the people gathered against Aaron and said to him, “Come, make us a god who shall go before us, for that man Moses, who brought us from the land of Egypt—we do not know what has happened to him.”

Aaron said to them, “Take off the gold rings that are on the ears of your wives, your sons, and your daughters, and bring them to me.”

And all the people took off the gold rings that were in their ears and brought them to Aaron.

This he took from them and cast in a mold, and made it into a molten calf.29 …30

When Aaron saw this, he built an altar before it; and Aaron announced: “Tomorrow shall be a festival of YHWH!”

Early next day, the people offered up burnt offerings and brought sacrifices of well-being; they sat down to eat and drink, and then rose to dance. (Exodus 32:1-6)

Of course, this infuriates Yahwa and Moses. Moses burns the calf31 and commands the “Levites” — conceived here, I think, as the sword-wielding people of Hur — to kill a bunch of people (Exodus 32:26-36:29 (E, I think, though it’s controversial)).

To me, this is a pretty clear polemic against the Aaronid priesthood, the Temple, and the decadent celebration that commemorated its completion. The single cast-metal calf in the story is a scaled-down version of the twelve large bronze oxen in front of the Temple; just as Aaron builds an altar in front of the calf, the actual Temple altar stood in front of the bronze oxen. I don’t think there ever really was a cult of the golden calf in ancient Israel; it was always just a fable.32

Elders and Prophets

In addition to criticizing the Temple and the state-sponsored priests for straying from proper Yahwism, the E narrative seems to criticize political centralization: Moses, realizing that he couldn’t address all the Israelites’ problems by himself, “chose capable men out of all Israel, and appointed them heads over the people…and they judged the people at all times: the difficult matters they would bring to Moses, and all the minor matters they would decide themselves” (Exodus 18:25-26 (E)). Yahwa even invests these tribal elders with some of Moses’ “spirit” — and not just them but also a couple of uncredentialled prophets:

Then YHWH said to Moses, “Gather for Me seventy of Israel’s elders of whom you have experience as elders and officers of the people, and bring them to the Tent of Meeting and let them take their place there with you.

I will come down and speak with you there, and I will draw upon the spirit that is on you and put it upon them; they shall share the burden of the people with you, and you shall not bear it alone. (Numbers 11:16-17)

…Two men, one named Eldad and the other Medad, had remained in camp; yet the spirit rested upon them…and they spoke in ecstasy in the camp.

A youth ran out and told Moses, saying, “Eldad and Medad are acting the prophet in the camp!”

And Joshua son of Nun, Moses’ attendant from his youth, spoke up and said, “My lord Moses, restrain them!”

But Moses said to him, “Are you wrought up on my account? Would that all YHWH’s people were prophets, that YHWH put His spirit upon them!” (Numbers 11:26-29)

The moral of these stories was that there were legitimate political and spiritual authorities that Solomon’s high-handed regime was disrespecting.

(The pro-prophet attitude, along with other clues, suggests to me that the E source emerged in the northern cultic center of Bethel, where, according the northern story of Elijah (set in the 800s BCE), there dwelt prophets important enough to have “disciples” (2 Kings 2:3).)

North and South Redux

The north/south conflict over legitimacy came to a head after Solomon died. The northern Israelites lobbied his successor, Rehoboam, to cut down on the taxes and forced labor; he refused; so, in 930 BCE, they seceded, ultimately forming the confusingly named Kingdom of Israel and leaving behind a rump Kingdom of Judah.

Judah was the less important and powerful of the two. This was vividly illustrated some 150 years later, early in the 8th century BCE, when King Amaziah of Judah, puffed up after defeating the Edomites, threatened King Jehoash of Israel. Bad idea:

King Jehoash of Israel captured King Amaziah…of Judah at Beth-shemesh. He marched on Jerusalem, and he made a breach of four hundred cubits in the wall of Jerusalem, from the Ephraim Gate to the Corner Gate.

He carried off all the gold and silver and all the vessels that there were in the House of YHWH and in the treasuries of the royal palace, as well as hostages. (2 Kings 14:13-14)

The Bible doesn’t explicitly say so, but I think that the “gold and silver” objects stolen by the northern kingdom included the huge gold-covered cherubim statutes in the Temple’s inner sanctuary, which, after Solomon commissioned them, were never mentioned again.

The Ark of the What?

Without the cherubim around it, the modest wooden footstool of God must have looked rather pathetic. This forced a rethink. Solomon’s reign had been a high-water mark of Jerusalem-centered grandeur; the Kingdom of Judah couldn’t afford to operate on the same scale. So the replacement cherubim were radically downsized, built into the top of the Ark instead of being freestanding statues:

At some point, the Ark’s function was also reconceived. It was no longer a royal footstool, since God was imagined less and less as a Really Big Guy. Instead, it was just a special container. But what was supposed to be inside it? That’s harder to answer than one might guess, as Liane Feldman says:

There are some Hebrew terms in the priestly narrative about the meaning of which we simply cannot be exactly sure; it is therefore nearly impossible to translate them into English. … One of the most significant examples of this comes in the story of Moses on Mount Sinai. When he descends from the mountain, he brings with him something called the edut. Later in the story, this edut is placed inside the ark that is itself placed in the inner sanctuary of the Dwelling Place.33

…Traditionally, it has been conflated with the tablets that Moses brings down from Sinai in the nonpriestly [E, but not J] story in the Pentateuch, but there is no evidence whatsoever in the priestly narrative that this should be understood as tablets. There are no laws given on Sinai in this story, and thus nothing to inscribe on tablets.

Feldman notes that “the Hebrew root behind this word means something like ‘witness’ or ‘testimony’”; Raanan Eichler argues that it probably means “pact” or “treaty,” as do multiple non-Hebrew Semitic words that seem to be its cognates.34 My guess is that, at first, the edut was supposed to be the scroll on which Moses wrote Yahwa’s loyalty-focused covenant in the J narrative, but, as the priestly ideology evolved further, the scroll fell out of the story and the edut became mysterious.

The Indignities Continue

Later in the 700s BCE, Solomon’s legacy took another hit. King Ahaz of Judah became a vassal of the Neo-Assyrian state; as part of his tribute obligations, he “removed the tank from the bronze oxen that supported it and set it on a stone pavement — on account of the king of Assyria” (2 Kings 16:17-18). So the 12 bronze oxen that had inspired the molten-calf story were now gone, either melted down for metal value or kept as trophies in Assyria.

At least the kings of Judah could be grateful that they weren’t the kings of Israel. In 723 BCE, the Assyrians captured their capital city, Samaria, and turned their territory into the province of Samerina. The kingdom of Israel was no more.

Ahaz’s successor as king of Judah, King Hezekiah, hoped to capitalize on the northern kingdom’s fall to boost Jerusalem’s prestige. He officially invited everyone to Jerusalem for Passover:

The couriers went out with the letters from the king and his officers through all Israel and Judah, by order of the king, proclaiming, “O you Israelites! Return to YHWH, God of your fathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, and He will return to the remnant of you who escaped from the hand of the kings of Assyria.” (2 Chronicles 30:6)

But this campaign was at best a partial success:

As the couriers passed from town to town in the land of Ephraim and Manasseh till they reached Zebulun, they were laughed at and mocked.

Some of the people of Asher and Manasseh and Zebulun, however, were contrite, and came to Jerusalem. (2 Chronicles 30:10-11)

Hezekiah’s outreach program also had a more militant side. As I discussed in Part 1, he was responsible for the destruction of Nehushtan, the bronze snake that Moses had made. Though the text isn’t explicit, I think that Nehushtan was probably kept at Bethel, just across the border in Assyrian Samerina.

He abolished the shrines and smashed the pillars and cut down the sacred post. He also broke into pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made, for until that time the Israelites had been offering sacrifices to it; it was called Nehushtan. (2 Kings 18:4)

In the Book of Kings, the Hebrew term used here for “Israelites,” vᵉnei-yisraʾel, usually refers to the people of the northern kingdom and occasionally to pre-monarchic Israelites in general — but never to the people of the Kingdom of Judah alone. (I went through and checked.) So I think it’s implausible that Nehushtan was in the Jerusalem Temple. It was a northern artifact, consistent with its presence in the E source and absence in the J and P sources.

But wouldn’t it have been a little aggressive for Hezekiah to cross the border into Assyrian territory, even if only to destroy a Yahwist relic? Yes. That’s why I suspect that it happened soon after the death of Assyria’s Sargon II, when many Assyrian vassals rebelled. Unfortunately for them, Sargon II’s son, Sennacherib, managed to consolidate his power and put them down:

After waging war against Babylonia, Sennacherib finally campaigned against the Levant in his fourth regnal year (701 BCE), entitled in his inscriptions his third campaign. According to these inscriptions, the submissive rulers of Phoenicia, Philistia, and Transjordan paid him tribute. He then conquered the rebellious kingdom of Sidon (and Tyre) and replaced its king, Luli, who fled to Cyprus. Sennacherib then marched south, conquered Ashkelon, and deported its king; he slew the officials and nobles of Ekron who had instigated the rebellion and reinstated Padi as its king; he defeated the Egyptian and Kushite forces in a pitched battle. Finally, after devastating most of the kingdom of Judah, its king, Hezekiah, capitulated and paid a huge penalty and tribute. Vast regions in the Judean Shephelah were stripped from the territory of Judah and given to the loyal Philistine kingdoms.35

There’s a lesson here: don’t mess with Nehushtan!

“I Have Found a Scroll of the Teaching”

Judah’s Assyrian vassaldom lasted around 100 years. After that, the kingdom had a new master: Egypt. Nadav Naʾaman has argued that this switch was part of an explicit deal between Assyria and Egypt: territory in the Levant “in exchange for military aid” against Babylonia.36 King Josiah of Judah exploited the dislocation to take back some of what Assyria had grabbed and even expand a little to the north and east, including into Bethel.37

It was then, I think, that the Judahite elite first encountered the E source — and it came as a shock. Beyond its unflattering depiction of Aaron in the molten-calf and other stories, the E source painted a picture of what Yahwa expected from the Israelites that was far different from what the southern tradition led people to believe. In the J source, Yahwa’s demands were simple: don’t obey other gods, and don’t make covenants with the non-Israelite inhabitants of Canaan. The whole explanation took four sentences.

In the E source, in contrast, there was a lengthy, detailed “covenant code,” covering many different aspects of life: violence, slavery, sex, witchcraft, and cultic practice, among other things. All these laws had, according to the E source, been written by Yahwa himself upon stone tablets held up by Moses.38

The Judahites may have been tempted to disbelieve what the E source said, but it seemed authentically ancient, because it was: if, as I suggested above, its earliest version dated to around the end of Solomon’s reign, then it was, at the time that King Josiah’s men came across it, 300 years old.

But there were some parts of E’s philosophy that the kingdom of Judah couldn’t accept. The idea that Yahwa looked kindly upon any old earthen altar didn’t sit well with the southern state’s ambition of centralizing all Yahwist worship at the Jerusalem Temple. And, though taking the Aaronid priesthood down a peg or two could enhance the king’s relative status, going too far down this path was dangerous. So the stories and laws of the E source were incorporated into the southern tradition in re-written, distilled, and toned-down form. This was the origin of the D source, which constitutes the bulk of the Pentateuchal Book of Deuteronomy. It was the D source that introduced the newfangled idea of the Ten Commandments — some 600 years after the time of Moses. (And now the Ark could take its final form: in the D source, instead of containing the mysterious edut, it holds the stone tablets of the Ten Commandments.)

The official story didn’t say that the E source was discovered during the Judahite conquest of Bethel. Instead, the D source — or, more likely, an earlier and shorter version of it, the Valediction of Moses aka the V source39 — was basically lying between the couch cushions:

In the eighteenth year of King Josiah, the king sent the scribe Shaphan son of Azaliah son of Meshullam to the House of YHWH, saying, “Go to the high priest Hilkiah and let him weigh the silver that has been deposited in the House of YHWH, which the guards of the threshold have collected from the people. And let it be delivered to the overseers of the work who are in charge at the House of YHWH, that they in turn may pay it out to the workmen that are in the House of YHWH, for the repair of the House…”

Then the high priest Hilkiah said to the scribe Shaphan, “I have found a scroll of the Teaching in the House of YHWH.” And Hilkiah gave the scroll to Shaphan, who read it.

The scribe Shaphan then went to the king and reported to the king: “Your servants have melted down the silver that was deposited in the House, and they have delivered it to the overseers of the work who are in charge at the House of YHWH.”

The scribe Shaphan also told the king, “The high priest Hilkiah has given me a scroll”; and Shaphan read it to the king.

When the king heard the words of the scroll of the Teaching, he rent his clothes.

And the king gave orders to the priest Hilkiah, and to Ahikam son of Shaphan, Achbor son of Michaiah, the scribe Shaphan, and Asaiah the king’s minister:

“Go, inquire of YHWH on my behalf, and on behalf of the people, and on behalf of all Judah, concerning the words of this scroll that has been found. For great indeed must be the wrath of YHWH that has been kindled against us, because our fathers did not obey the words of this scroll to do all that has been prescribed for us.” (2 Kings 22:3-13)

Generations of skeptical readers have understandably viewed this scene as phony — what, they just happened to find the scroll in some dark corner of the Temple during spring cleaning? Wasn’t this just King Josiah’s pretext for imposing reforms he already wanted? Perhaps, but I suspect that the original freak-out over the E source (as opposed to the staged freak-out over the V source) was genuine. King Josiah didn’t need to take things as far as he did; I think he really did fear Yahwa’s wrath:

At the king’s summons, all the elders of Judah and Jerusalem assembled before him.

The king went up to the House of YHWH, together with all the men of Judah and all the inhabitants of Jerusalem, and the priests and prophets—all the people, young and old. And he read to them the entire text of the covenant scroll which had been found in the House of YHWH

The king…solemnized the covenant before YHWH: that they would follow YHWH and observe His commandments, His injunctions, and His laws with all their heart and soul; that they would fulfill all the terms of this covenant as inscribed upon the scroll. And all the people entered into the covenant.

Then the king ordered the high priest Hilkiah, the priests of the second rank, and the guards of the threshold to bring out of the Temple of YHWH all the objects made for Baal and Asherah and all the host of heaven. He burned them outside Jerusalem in the fields of Kidron, and he removed the ashes to Bethel.

He suppressed the idolatrous priests whom the kings of Judah had appointed to make offerings at the shrines in the towns of Judah and in the environs of Jerusalem, and those who made offerings to Baal, to the sun and moon and constellations—all the host of heaven.

He brought out the [image of] Asherah from the House of YHWH to the Kidron Valley outside Jerusalem, and burned it in the Kidron Valley; he beat it to dust and scattered its dust over the burial ground of the common people.

He tore down the cubicles of the male prostitutes in the House of YHWH, at the place where the women wove coverings for Asherah.

He brought all the priests from the towns of Judah [to Jerusalem] and defiled the shrines where the priests had been making offerings—from Geba to Beer-sheba. He also demolished the shrines of the gates, which were at the entrance of the gate of Joshua, the city prefect—which were on a person’s left [as he entered] the city gate.

The priests of the shrines, however, did not ascend the altar of YHWH in Jerusalem, but they ate unleavened bread along with their kinsmen.

He also defiled Topheth, which is in the Valley of Ben-hinnom, so that no one might consign his son or daughter to the fire of Molech.

He did away with the horses that the kings of Judah had dedicated to the sun, at the entrance of the House of YHWH, near the chamber of the eunuch Nathan-melech, which was in the precincts. He burned the chariots of the sun.

And the king tore down the altars made by the kings of Judah on the roof by the upper chamber of Ahaz, and the altars made by Manasseh in the two courts of the House of the LORD. He removed them quickly from there and scattered their rubble in the Kidron Valley.

The king also defiled the shrines facing Jerusalem, to the south of the Mount of the Destroyer, which King Solomon of Israel had built for Ashtoreth, the abomination of the Sidonians, for Chemosh, the abomination of Moab, and for Milcom, the detestable thing of the Ammonites.

He shattered their pillars and cut down their sacred posts and covered their sites with human bones. (2 Kings 23:1-14)

Of course, one of the fascinating things about these verses is the way that they reveal, in passing, how many unorthodox practices had been going on all along. An image of Asherah (Mrs. God) in the Temple? Cubicles for male prostitutes in the Temple? Chariots of the sun? Eunuchs? Alas, the Bible doesn’t have much more to say about such matters.

The great irony, if my theory about the molten calf is correct, is that what began as a northern critique of the southern cult transformed into a southern critique of the northern cult — and a just-so story to explain the Assyrian destruction of the northern kingdom. The authors of the E source had been mad about the extravagance of the Solomonic Jerusalem cult, with its golden cherubim and bronze oxen, made possible by oppressive taxation and corvée. But, by the 600s BCE, the cherubim and oxen were long gone, and the Jerusalem authorities no longer recognized the calf fable as an attack on them. Instead, they claimed that it was the old northern kingdom, starting under its first king, Jeroboam I, that had worshipped bovine statues at the cities of Bethel and Dan and had ultimately paid the price. When Deuteronomistic scribes in Judah wrote the history of their northern brethren, they blamed everything bad on a calf cult that never actually existed.

Anti-Climax Redux

With Yahwism back on firm footing, purged of unorthodoxy by the great King Josiah, Judah had a bright future ahead of it, right? No. Under murky circumstances, Josiah was killed by the Egyptian pharaoh, perhaps for being an uppity vassal. Not longer after that, in 586 BCE, the Babylonian army swept through and destroyed the Temple and the Judahite state. Many Judahites were taken into exile. The era of Israelite monarchies was over.

Babylon appointed as governor of “Yehud” a man named Gedaliah, who happened to be the grandson of Shaphan the scribe — the same Shaphan who had brought the “scroll of the Teaching” to King Josiah.40 This little accident of Babylonian imperial administration is probably why we have the Bible today. Gedaliah, scion of a great family of scribes, was uniquely positioned to preserve the J, E, P, and D sources, even as many of his fellow Judahite elites languished in exile.

In another lucky break, the exile ended pretty quickly. In 539 BCE, the Persian ruler Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon and assumed control of its empire, including Yehud. The Persians had a lighter touch than the Assyrians or Babylonians. Many exiles returned, and a new temple was constructed in Jerusalem.

It was under the Persian governorship of Nehemiah, I think, around 430 BCE, that scribes decided to fuse J, E, P, and D into a single chronologically organized text: the Pentateuch.41 We can, perhaps, sympathize with their motivations. Having four different independent but heavily overlapping accounts of history up till the time of Moses (and a little bit beyond, since I think J, E, and P all extended into parts of what became the books of Joshua and Judges) was confusing and unwieldy. Unfortunately, when those four accounts were combined, the result was also confusing and unwieldy — unreadable, one might say,42 notwithstanding the odd fact that it’s probably the most read text of all time. But the compilers of the Pentateuch were so conservative in their approach — attempting, whenever possible, to use the exact words of their sources43 — that, more than 2,000 years later, we can undo their hard work.

Once formed in the southern province of Yehud, the Pentateuch spread to the northern province of Samaria via intra-imperial politicking. Sanballat, the governor of Samaria (and thorn in the side of Nehemiah), had his daughter marry Manasseh, the son of the high priest of the rebuilt Jerusalem temple, and made Manasseh the high priest of a new, rival temple on Mt. Gerizim.44 Manasseh must have brought the proto-Pentateuch with him, which explains the origins of the Samaritan Pentateuch. (Samaritans, unlike Jews, don’t regard the non-Pentateuchal parts of the Bible as canonical. They’ve tweaked the text of the Pentateuch a little bit but mostly copied it faithfully — in a few cases, more faithfully than the Jewish Masoretic Text.45)

And then, in 332 BCE, Alexander the Great gained control of the Levant, inaugurating the Hellenistic era there. Before long, the Pentateuch was translated into Greek: the Septuagint.

Thus, after a 600-year period of gestation — from around 1040 BCE, when the J source started taking shape, to around 430 BCE, when the four sources merged — the Pentateuch became canonical quite quickly, in the form in which it still survives. It’s an extraordinarily strange beast. But now I can see more clearly how it managed to capture the attention of so many intellectuals for so long. At every turn, it almost makes sense, but not quite; it almost coheres, but then doesn’t. Figuring out how and why it has this character is, for a certain kind of person, an irresistible puzzle.

See Schmitz 2016, “Philistine PTG̊Y, Greek *ΠΕΝΤΑΓΑĨΑ ‘Five Lands’: Contact Effects in the Royal Dedicatory Stela from Ekron”: “It appears that Philistines of the Pentapolis by the 7th century BCE spoke a Canaanite dialect…An earlier ‘Aegean Philistine’ (probably a dialect of Greek)…was replaced over time by a ‘Philistine Canaanite’ language…The evidence indicates that, compared linguistically, Philistine shares features with the Byblos dialect, although taken as a system it remains somewhat distinct from all the other Canaanite dialect.”

Judges 1:16: “The descendants of the Kenite, the father-in-law of Moses, went up with the Judahites from the City of Palms to the wilderness of Judah; and they went and settled among the people in the Negeb of Arad.”I think much of the material in Judges about Caleb and Achsah are from J, but I’m not sure how common a view that is.

Some have claimed that there was no city of Kiriath-arba for the Judahites to take over, but I think this is false. See Chadwick 2019, “Hebron in the Late Bronze Age,” in The Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Southern Canaan: “The combined finds of the American Expedition to Hebron suggest that Tell er-Rumeide was the site of an active populated city during the Late Bronze Age, surrounded by a city wall that had been built in MBII. … It cannot be claimed that biblical tradition is unreliable because there was no LB Hebron, because there was indeed a thriving city there.”

See also Naʾaman 1981, “‘Hebron Was Built Seven Years before Zoan in Egypt’ (Numbers XIII 22)”: “In my opinion, the ‘building’ of Hebron and Tanis in our verse refers to the rebuilding of these cities as capitals of their respective kingdoms, Israel and Egypt. … The root bnh (‘to build’) is intimately connected with the foundation of a new capital city in several biblical verses.”

Roughly the midpoint between (a) the foundation of Zoan/Tanis (in the reign of Smendes, using the radiocarbon-based accession-date range in Manning 2014, A Test of Time and a Test of Time Revisited, Table RE11 and (b) the beginning of David’s reign in Hebron (starting with the dates in Mahieu 2022, “A Revised Chronology for the Kings of Israel and Judah,” and working backwards).

1 Chronicles 15:16. The Book of Chronicles is quite late, but to my eye this section appears to draw on genuine ancient sources (hence the long list of boring names that follows).

I’m fond of the idea that the scene in Joshua 10:13 in which “the sun halted in midheaven” during a battle preserves a memory of a total solar eclipse in 1131 BCE. There are other eclipse candidates, though. See Khalisi 2021, “Joshua’s Total Solar Eclipse at Gibeon.”

I think Hur’s lineage stayed east of the Jordan, where the P source’s Merarite cities were located, while Moses’ lineage was in the west and north, where the Gershonite cities were located. See Wikipedia on “Levitical city.”

As presented in Seri-Levi 2023, “The Yahwistic Account of the Theophany at Sinai,” and extracted from Exodus 34:10-28 (J).

I suspect that the strange story of Micah’s house in Judges 17-18 was intended in part to besmirch Bethel and Dan, yet it also discloses that “Jonathan son of Gershom son of Moses” was affiliated with both “Micah’s house” (Bethel?) and Dan. (For what it’s worth, I thought this before finding the same argument in Amit 2000, Hidden Polemics in Biblical Narrative, chapter 1.) At some point there was an attempt to replace Moses with Manasseh in Jonathan’s lineage to avoid this awkwardness: see e.g. the JPS translation (noting that the way “Manasseh” was written “indicat[es] an an earlier reading ‘Moses’” and a fuller explanation from Holm 2014, “Moses in the Prophets and the Writings of the Hebrew Bible”:

An interesting case concerning Moses’ descendants is in Judges 18:30, where members of Moses’ family line are described as priests for the tribe of Dan at the city of Dan. The Danites steal an ephod, the teraphim, the idol, and a priest from the house of Micah, and they then go to Laish, burn it down, and rebuild it as Dan: “Then the Danites set up the idol for themselves. Jonathan son of Gershom, son of Moses, and his sons were priests to the tribe of the Danites until the time the land went into captivity.” The text of this verse was corrected by a later insertion of a nun consonant to turn Mšh (Moses) into Mnšh (Manasseh). An inserted nun may be unnecessary, since the correct reading “Moses” reflects traditions elsewhere (e.g., 1 Chron. 23:14, in which Moses’ sons or Levites are divided up into three courses for serving in the temple). Another possibility, however, is that the later editor who inserted the nun is trying to spare the name of Moses from being associated with forbidden, non-Yahwistic worship.

Redford 1992, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, p. 419: “Apart from ‘Moses’ the only [personal names] that are indubitably of Egyptian origin are Hophni and Phinehas, and once again we find ourselves in a certain milieu at Shiloh, with a priesthood explicitly stated to date from the time of the Bondage.”

Finkelstein and Piasetzky 2009, “Radiocarbon-Dated Destruction Layers: A Skeleton for Iron Age Chronology in the Levant.” 1060 BCE is the (rounded) midpoint of the stated calibrated date range of “1081–1032 BC according to the Bayesian model.”

In the official story in 1 Samuel 4, the Philistines attack around Aphek/Eben-ezer; Hophni and Phinehas bring the Ark to the battlefield and get killed; and Eli dies of grief back in Shiloh. Thus Shiloh isn’t actually touched. But, based on the allusions to the destruction of Shiloh itself in Psalm 78 and Jeremiah 7 and 26, along with the archaeology, I don’t buy this.

See Leuchter 2006, “The Reference to Shiloh in Psalm 78.”

That Kiriath-jearim was broadly Aaronid/Kohathite isn’t directly stated in the Bible, but it was Judahite (see Levin 2021, “Was Kiriath-jearim in Judah or in Benjamin?”), and it’s striking that Abinadab, whose “house…on the hill” contained the Ark (1 Samuel 7:1), seems to have been named after Nadab, one of Aaron’s sons. Levin 2021 mentions this in n. 14: “A connection noted by Blenkinsopp…: ‘Names formed with -nadab are of frequent occurrence in the levitical cult service…’”

There are a few ark references in the reconstructed J source, but they all seem like late additions to me. For the replacement of Hobab with the ark, see Seebass 1964, “Zu Num. X 33f.” For the Song of the Ark (Numbers 10:35-36), see e.g. Dershowitz 2021, The Dismembered Bible, p. 12ff. (“According to these traditions, the Song of the Ark was marked off with dots rather than inverted nunim, but the point remains the same: something is awry”).

Again, starting from the dates in Mahieu 2022, “A Revised Chronology for the Kings of Israel and Judah,” and working backwards.

See Baden 2013, The Historical David: “David became king and found himself in possession of a capital with no religious significance. Jerusalem had a cult before David, but it was not an Israelite cult because Jerusalem was not an Israelite city. … What he needed was something tangible, something everyone would recognize as marking God’s presence. And the ark was just a few kilometers away. … David took it — and it is likely that he took it by force. According even to the biblical account, before going to Kiryath-jearim David ‘assembled all the picked men of Israel, thirty thousand strong; then David and all the people that were with him set out’ (2 Sam. 6:1–2).”

See Baden 2013, The Historical David, or just read the biblical account of Nabal with an iota of skepticism.

Presented and remembered as David’s son, though Baden 2013, The Historical David, convincingly argues that he was actually Uriah the Hittite’s son.

Compare Numbers 4:24-28 to Numbers 4:31-33.

Feldman 2023, The Consuming Fire, p. 24.

Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2019, “The Temple of Solomon in Iron Age Context,” gives the basics. A more detailed treatment is in Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016, Solomon's Temple and Palace: New Archaeological Discoveries.

Feldman 2023, The Consuming Fire, p. 91, n. 6.

Eichler 2021, The Ark and the Cherubim.

I first saw this image in Eichler 2021, “Solomon’s Throne in Its Ancient Near Eastern Context.”

See Richelle 2020, “Did Solomon ‘Overlay the Whole Temple with Gold’? A New Look at 1 Kings 6:20-22”: “if this new proposal is correct, there is an important consequence with regard to the contents of the text: the earliest form of 1 Kings 6 did not assert that all the walls of the Temple were overlaid with gold; it was only the case of the Debir. The notion that ‘the whole house’ was gilded (v. 22a) seems to have been introduced secondarily in the text by a redactor.”

JPS 1985 translation: “tank of cast metal.” Other translations: “‘sea’ of cast metal,” “Sea-Basin.”

This is the standard JPS 1985 translation, but I’m persuaded by VanDyke 2022, “Designing the Golden Calf: Pens and Presumption in the Production of a ‘Divine’ Image,” that a better translation would be “and he designed it with a rush pen and made it into a cast-metal calf.”

The “This is your god, O Israel” line seems like an obvious later insertion, copied over from the Deuteronomistic Jeroboam account.

In the canonical version of the story, he also forces the Israelites to drink water mixed with ground-up molten calf, but, following Frankel 1994, “The Destruction of the Golden Calf: A New Solution,” I think it’s more plausible that, in the original version of the story, Moses ground up the shattered stone tablets of the Covenant Code.

For an early example of a scholar struggling with the thin biblical evidence for an actual practice of golden-calf worship, see Paton 1894, “Did Amos Approve the Calf-Worship at Bethel?” The Book of Hosea seems to allude to golden calves, but I think it’s a relatively late, post-Deuteronomic work. See Smith 2018, “The ‘Wilderness’ in Hosea and Deuteronomy: A Case of Thematic Reappropriation”: “it is argued that Hosea follows after and is dependent on a well-developed Deuteronomic tradition that substantively resembles the canonical book of Deuteronomy.”

Feldman 2023, The Consuming Fire, p. xxii.

Eichler, The Ark and the Cherubim, p. 128.

Kahn 2020, Sennacherib’s campaign against Judah : a source analysis of Isaiah 36–37, p. 1.

Naʾaman 1991, “The Kingdom of Judah Under Josiah.”

Naʾaman 1991, “The Kingdom of Judah Under Josiah,” still seems to be the best source on this stuff, but see also Sergi 2023, “The Kingdoms of Israel and Judah,” in The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: The Age of Assyria, p. 1182-7.

See Orstav 2023, “The Second Ascent of Moses for the Inscription of the Tablets.”

See Dershowitz 2021, The Valediction of Moses — a remarkable book on several levels.

See Werse 2019, Reconsidering the Book of the Four, p. 334-6.

Yoo 2017, Ezra and the Second Wilderness, was my main source on the Ezra/Nehemiah stuff.

Probably driven in part by practical, material consideration. See Dershowitz 2021, The Dismembered Bible: Cutting and Pasting Scripture in Antiquity.

See Dušek 2012, “Archaeology and Texts in the Persian Period: Focus on Sanballat,” and Dušek 2007, Les manuscrits araméens du Wadi Daliyeh et la Samarie vers 450-332 av. J.-C., which was very helpful even though I can’t read French.

See e.g. Crawford 2022, The Text of the Pentateuch, p. 170-1.